Leia o texto em português aqui.

Warning: SPOILERS ahead for ALL seasons of Dark!

Some corrections on April 8th – huge thanks to ManifoldMold on Reddit

Even as it deals with secret societies and apocalyptic technologies in 20th-century Germany, it’s curious that Dark, Netflix’s acclaimed show, completely ignores the nazis. This does not necessarily impair the narrative, but hints at how hard it is to analyse it politically. Its ponderings over free will, for instance, follow a more properly “psychological” or “philosophical” line of enquiry, that many already explore well. Might there be something political to say about it?

It is easy, and technically correct, to say that “everything is political”, but it isn’t much help. Part of Hannah’s arc, for instance, has to do with her becoming less emotionally dependant on men. Her decisions, however, depend on the culturally conferred autonomy she’s got; furthermore, it matters that the show’s creative team thought that this story could be told; that it would be well received. In other words, the very existence of her arc depends on broader political questions, but we’re merely talking about the fact that the narrative is a product of the cultural industry and is set on, was produced in, is consumed in, the 21st century (and not, say, the 15th). This doesn’t mean much. Certainly doesn’t mean that the show is feminist in any substantive meaning of the word – at least not for that reason.

Of course some works of art are more explicitly political than others. Politics and Dark are not a “perfect match”. However, I do think there are interesting things to explore in that relationship. The show features human interactions and conflicts that are resolved in a certain way; being a scientific fiction, these matters are explored using terms and concepts from the hard sciences[1], but my intention with this text is, in a way, to “translate” this language into a political theoretical one, analysing what Dark has to say on the matter, even if it does that unintentionally.

This implies two things.

- Before we deal with the politics, we must talk about the scientific concepts the show plays around with, to speculate on what exactly happened in it[2]. You may go straight to the part on politics, but you might not understand a few things I say about the sequence of events in the show – and if you try to read the text only from that part on, you might not get why I think certain scientific concepts used by the show imply that things happened the way I think they did.

- As my understanding of physics is extremely limited, this argument may be partially incorrect. My hope is that the show’s poetic license in dealing with exact science “cancels out” my mediocre understanding of the matter. Maybe at least my ordering of the events of the show will be self-consistent – and my political reading of them, inspiring.

Table of contents

- Dark and the science of time travel

- What is time?

- The possibility of going back to the past

- Introducing determinism

- The possibility of (deterministic) time travel

- The universes of Adam and of Eva involve CTCs

- It’s hard to understand CTCs as one lives them

- Introducing indeterminism

- Interpreting quantum physics

- No, Dark’s got nothing to do with Many Worlds Theory

- What it’s like to live in Winden

- Tannhaus’s plan

- The effect of Tannhaus’s machine

- Tannhaus’s machine’s (possible) internal logic

- What is the “knot”?

- The particle-universe duality

- Entangled universes

- Two superpositions

- The paradox in what we’re told about the ending

- The Copenhagen ending

- The Advanced Action ending

- Reinterpreting the events

- Claudia’s strategic choice

- Understanding the parallel realities

- Reframing what we see on screen

- What happens at the apocalypse in Eve’s world

- The possible roles of Claudia 1

- The duplications at the third apocalypse

- Did Claudia 1 meet Claudia 2?

- Claudia Tiedemann’s last lie?

- The return of the triquetra

- The political philosophy of Dark

- “The whole thing is wrong.”

- Samantha Fox and the age of latency

- The problem was not listening to anybody else

- The victory of the authoritarian principle

- The unavoidable war between light and shadow

- The underside of love

- The three basic attitudes toward wickedness

- Breaking the cycle

- Advanced action and counterpower

- The end is the beginning

Dark and the science of time travel

There are three things in the show whose connection, even after the final episode, remains elusive: how Original World Tannhaus’s machine works, what was the nature and the dynamics of Adam’s and Eve’s worlds, and what happened at the end, when the latter universes[3] disappear to “fix” the former. The answer to each of these questions helps to sketch the answer to the others (“everything is connected!”).

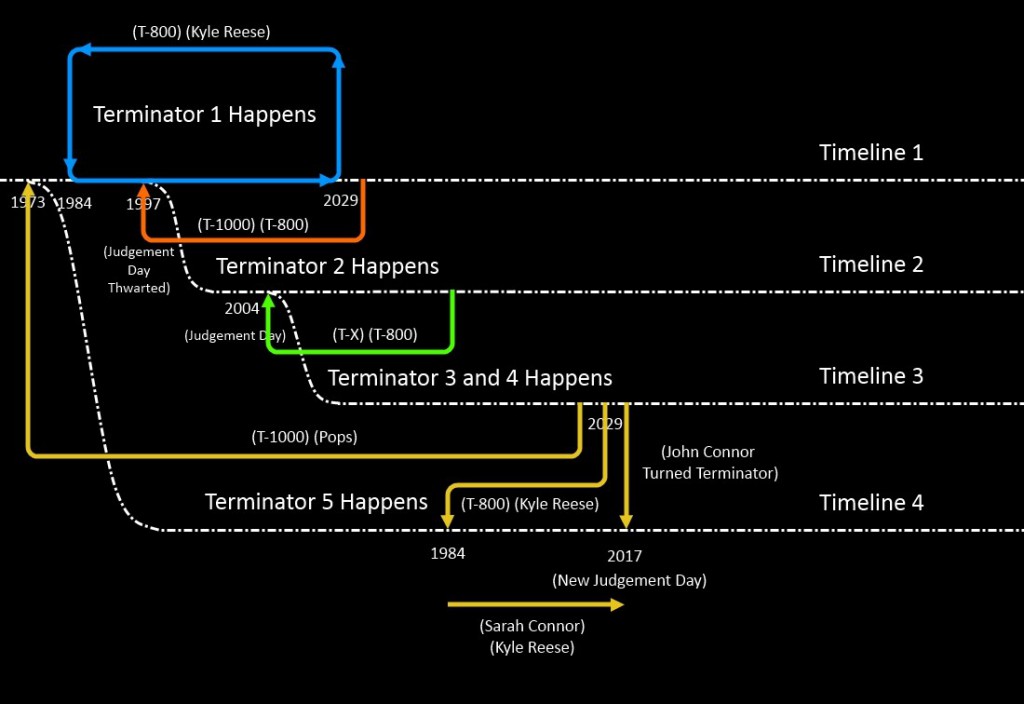

Why hasn’t the show answered everything satisfactorily? Consider the following: if Jonas and Martha, whose existences depend on the car accident that led Tannhaus to create his machine, go back in time to prevent the accident and are successful, the accident has to happen (cannot be prevented) so that it can be prevented[4]. Claudia tells Jonas (Adam) that she had also used the apocalypse to move herself in another direction – but where’s “Claudia 2”? [5] If every “cycle” can only happen due to the occurrence of all others, it doesn’t make sense to think of a series of cycles, much less of the idea that things can change. The chain of cause and effect is broken for a fraction of a second in the apocalypse; Eva knows this, and makes use of this resource. But the Martha who becomes two in Adam’s apocalypse doesn’t know it. How does she “duplicate herself”, then, if that’s a matter of using free will? Why only Jonas and Martha, who knew nothing about it, “get duplicated” at that moment? Why isn’t there a second version of each person in the entire world who went through the apocalypse? More: if cause and effect are broken, then there is not only the possibility of making a “different” choice, but absolute randomness. In each fraction of a second, each time the cycle repeats – and, if we’re to believe Claudia, it has happened thousands of times – each Martha might have made a different decision and therefore multiplied herself thousands of times. Certainly there would have been more than two Marthas. One saved Jonas, the other went back with Bartosz, the other hid somewhere else and survived having done nothing of the sort, the other died, the other came back with Bartosz but didn’t become Eva, etc. In fact, if cause and effect “cease to function”, nothing’s stopping Martha from suddenly becoming Zac Efron from one moment to another. Yet, at each repeated moment, Martha must choose only the two things that originate the series of events that have originated that moment – if she doesn’t do that, that moment wouldn’t be able to happen at all. What does the interruption of time and of the relation of cause and effect have to do with two things happening at the same time?

REMARK 1: You cannot suppose that in one “cycle” Martha chooses something and in the “next” one she makes a different choice. Every time Martha chooses to come back with Bartosz, Eva makes her kill the Jonas that could only be there if the Martha who chooses to save him had already done that. So it is not a matter of alternating choices by cycle; the Marthas really do “multiply” there.

Later, I’ll make several “informed guesses” about things that must have happened, but were not shown on screen. I believe this happened for a few reasons. Recording fewer scenes is cheaper for Netflix. It also enables the show to sweep under the rug features of the story which would make the ending less “heroic”. The “seeds” left by the narrative (such as Claudia saying she had used the apocalypse, instead of a scene that shows her doing so) are enough to allow for speculation about what happened without demanding that everyone follow every detail. Hence it was good strategy: most people enjoy the ending, and only a few obsessed nerds strive to get into the rabbit’s hole to follow the clues to the end. If you want to know where I got by doing that, let’s start by talking about time.

What is time?

The perspective that may best represent the common sense on time is called presentism. We live only and always in the present, and both future and past don’t really “exist”. It’s like messing around with Play-doh: there can only be one “state of things”, one way for it to be arranged at a time, and “time” by the way is a reference to the series of transformations it suffers from one state of things to another.

However, you can model play-doh at different speeds. Does time flow faster or more slowly? It doesn’t make sense; this seems like a (circular) attempt at avoiding an explanation for what time is. In turn, the “growing block” perspective sees the passage of time as some sort of accumulation of past[6]. It’s like building a tower; the floors higher than the one you’re building now don’t exist yet, but the ones you’ve already finished remain under you. The theory of the “universal block”, however, also known as eternalism, holds that “all existence in time is equally real” – that is, including the future. “Moving in time” is simply like going from one place to another. When you’re home, the other places don’t cease to exist. They’re still “there”, it’s just you that is not at them. The same applies to future events.

The possibility of going back to the past

In a way, presentism cannot entail time travel, as there would be no other time to travel to in the first place. Since only the “now” exists, travelling to the past could only mean transforming the entire universe until it is made to be the exact same way it was in the moment you’d like to go back to. Growing block theories, on the other hand, support trips to the past, albeit in a weird way. An interesting example is my own Brazilian Portuguese novel M10, but perhaps a better known example is the movie Edge of Tomorrow (based on the manga All You Need is Kill). The past comes into being as the present advances, and is therefore conserved; hence it would be possible to visit it. However, as there could only be a single point of reference – the “now” – this means that visiting it means retarding the entire “now”, erasing everything that had already happened after the point in time you’re going back to. In the metaphor of the tower, it’s as if you had to “undo” the floors you had already built until you got to the floor you wanted to get to (because you can only be at one floor at any time, and no floor above the one you built can exist). Going back in time, in this case, if it weren’t instantaneous, would be like that Coldplay video:

The thing is that general relativity makes it harder for us to see the “now” as a “privileged” moment, since time depends on the frame of reference. While both presentism and the growing block theory assume that we’re all living together at the same point in time, one that always goes ahead toward the same direction (the future), general relativity has already shown this isn’t exactly the case. Every element, every object, every person, has a worldline, which is the path it goes through in spacetime (that’s what that Donnie Darko scene tried to represent). It’s not time that passes; we’re the ones passing through time, each one with their own worldline, which can even go through “time deformities”. Interstellar has an interesting and 100% scientific example: if you land on a planet close to a black hole, each hour there equals seven years on Earth. That is, gravitational deformities allows people to go from point “year 2000” to point “year 2007” in an hour (in “local time”), while worldlines that are not affected by this deformity still take 7 years to go from the first to the second point. Besides, relativity also allows us to doubt that time always moves in the same direction, that is, there is nothing[7] in the universe that forces a worldline to always go towards the same direction in the map, that is, towards the “future”.

“The distinction between the past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion” – Albert Einstein

Within the growing block theory it wouldn’t be possible to make the entire “now” go back; in practice, therefore, time travels would make almost as little sense as they do within the framework of presentism. Eternalism, however, suffers from the opposite problem: if time travel is possible, why can’t we just do it? Although “travelling”[8] in time in the relativistic sense is a common occurrence (the GPS in our phones wouldn’t work without taking that into account), why can’t we, for instance, tell our past selves what were (will be) the lottery numbers?

Introducing determinism

For starters, deforming spacetime that much, in such a specific way, would require physical conditions that are very unlike the ones we find here on the surface of planet Earth. I’ll come back to that soon. Let us first discuss an important philosophical reason: determinism. Worldlines are like chains linking every moment of an element to its next one. Every cause has a consequence, and vice versa. Ever since the universe began the way it did, each moment has been causing the next one in such a way that an unimaginable quantity of energy would be necessary to “cause” a movement of all matter that would take it “back” in the time dimension. Nothing in the chain of events from the origin of the universe allows us to imagine that something like that could happen around here. In other words, you could theoretically move to the past in the time dimensions, but in practice, the initial conditions of the universe (the Big Bang) went on causing the next conditions in a deterministic fashion, and we are the necessary product of that logical line.

“God does not play dice” – Albert Einstein

Determinists presume that, if we had all information about all of reality – about all atoms, energies, everything – we could know for sure how the future would be. Determinists might even accept that we’ll never be (biologically, cognitively, computationally) capable of actually calculating the future with such level of detail, but they cling to the idea that it is already determined nonetheless. Deep down, everything boils down to conservation of matter, of energy, and all sorts of rigid natural laws that make it the case that every cause has only one consequence and vice versa. On the other hand, if we can’t predict the future due to lack of information, that isn’t always the case with the past. We can, for example, say that if I could, at some time in the future, go back to make myself win the lottery last week, I would already have done that, because “last week” already happened, it’s a point in timespace that’s already determined.

The possibility of (deterministic) time travel

If in practice the eternalist perspective explains why time travel hasn’t happened yet or why it’s probably impossible, the mathematical possibility still exists. As determinism is still a condition – since every cause must have a consequence, and vice versa – to think of a worldline (or system of worldlines) whose trajectory leads to a point in time in the past implies a “circular” route: the past must cause that in the future the worldline returns to this same past, just as the future must cause that in the past the worldline goes to that same future.

For that reason, eternalist time travelling means a wordline that constitutes a closed timelike curve (CTC). As Leo Stein explains, a CTC “is a trajectory that’s perfectly normal everywhere, always sticking to the rules of moving in a timelike direction, always going (locally) forward in time, and yet ends up back where (and when) it starts”. This scenario is possible if “spacetime has a strange geometry”; as we have seen above, deformities – read: curves – in the fabric of time are caused by differences in gravity. The idea is to imagine a gravitational deformity so colossal that worldlines close themselves in a circle. As this The Great Courses Daily class explains, such “weird geometries” could be caused by rotating black holes or by – here we go! – wormholes.

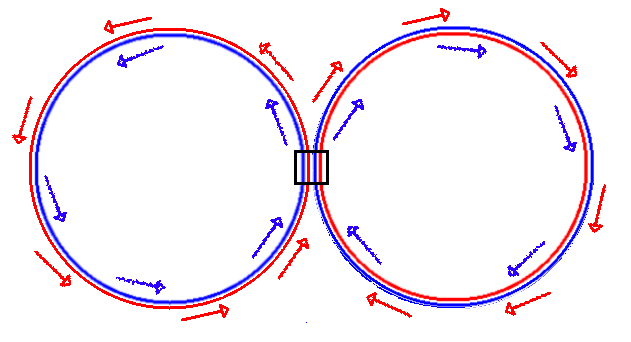

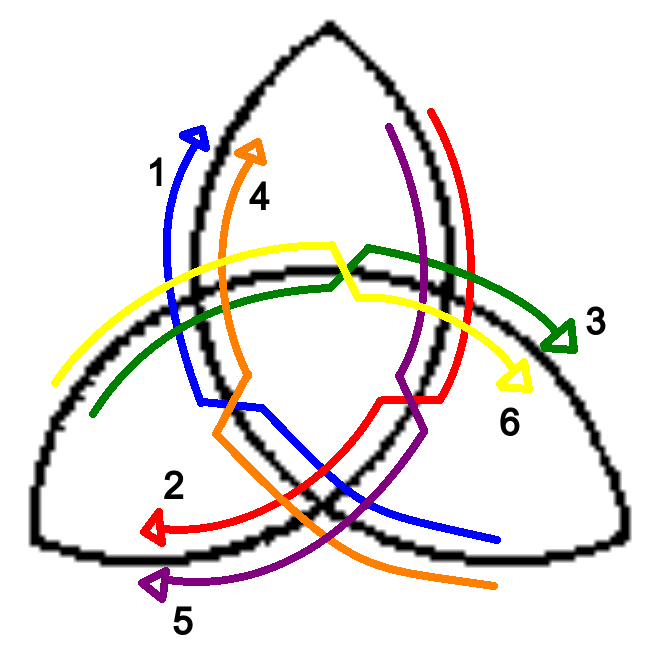

In a CTC, time goes “forward”, but the point where it goes toward might be a point in the past. See figure 2 below: it’s like going around a circle until a point “before” where you were: this point will be at the same time a point “after” where you were, simply because that is the relation between any two points in a circle!

The universes of Adam and of Eva involve CTCs

In the show, we see again and again that, as in a circle, “the beginning is the end”. There isn’t “an origin” to what happens. Tannhaus’s book in Adam’s world isn’t the only example of the onthological (or “Bootstrap”) paradox; the show is full of them, including The Unknown’s very family tree (he’s his own greatgreatgreatgrandfather on his father’s side and greatgreatgrandfather on his mother’s). One of the most notable effects of this circularity is that, since people can go back in time, the future also influences the past, and if the future (a consequence of the past) exists, then the past must, by logical necessity, be the same – just like the future, which has to have already happened since it influenced the past. There isn’t an origin within the circle. In a universe with CTC time travelling, nobody can “change” anything by going to the past. CTCs are deterministic time travels. In the future, things will happen that will cause things in the past, and therefore it is not only the past that cannot change, but also the future: the future becomes a form of past.

We can hence make basic assumptions about the way time works in Adam’s and Eve’s universes in Dark. Going back in time isn’t like in the growing block theory: past and future are always “there” to be “visited”. They have to be. The future must have some “materiality”, since it already influenced the past (again: the future becomes a form of past). When Hannah goes from 2020 to 1987, she doesn’t get younger; her (local) time is kept, that is, if she stayed a couple of hours there, she in fact got two hours older, even though she was in another year. Therefore, the worldlines always go “ahead”, even if “ahead” means a point in the past. The show’s own official website represents time travel with semicircles, not with arrows indicating people going “back” in the timeline (see figure 3 below). Besides, causality seems to be rigidly maintained; everything one goes back in time to do has already happened, because it was part of the causes of that trip to the past. Depending on how far back you go, you end up going through the same time you’ve already lived before, albeit with a different perspective. However, if that’s not the case (if you go back to a time way before you were even born, for instance), you’re still causing the causes of you being born and of you having grown up in such a way to have come where you are now.

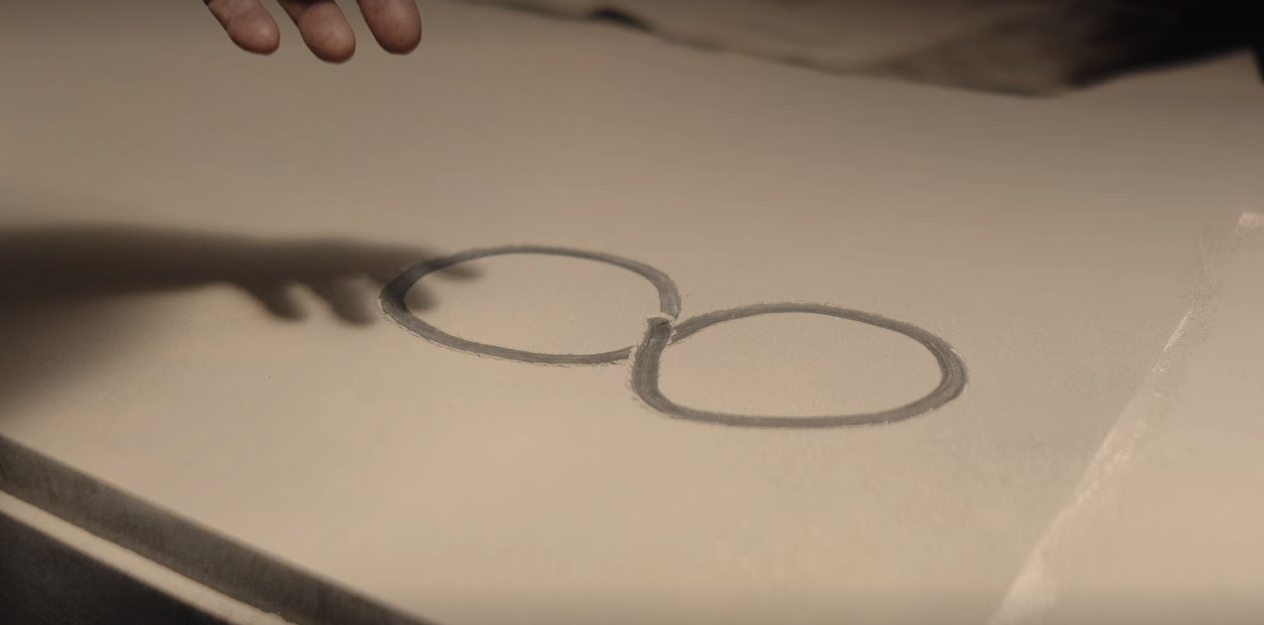

REMARK 2: When we speak of a “circular” time, we’re using the circle as the simplest representation of a line that closes in on itself (without a beginning or an end); any bidimensional geometric figure without loose ends (a square, a diamond, a triangle, etc.) would work just as well to represent the idea of a CTC (not in the mathematical-physical sense; only in the philosophical one we need here). We’ll need figures that are more internally complex than a circle to talk about Dark – moving forward we shall analyse, for instance, the “infinity symbol” Eva uses to explain what happened at the 2020 apocalypse in Adam’s world (Figure 6 below).

It’s hard to understand CTCs as one lives them

We however don’t feel the circle as a circle – as said above in Stein’s definition, the movement is “perfectly normal everywhere”. The experience of living seems linear, because you’re always going ahead in time. As Jonas goes through the same point in time twice (in a CTC), he thinks the event “happens” twice, but it only happens once. It’s like leaving a house and entering it again, with it in the same state, and thinking that it must be somewhere else on the map. Several worldlines can go through the same point in time; it’s still a single point.

Imagine that (in Dark‘s time logic) you decide to visit a party sometime in the past. You travel there once when you’re 20, then return to when you came from; then again, when you’re 30, and again when you’re 40, and so on and so forth. Each time you travelled, you’d arrive there and would see the other “you”s (the 30-year-old, the 40-year-old, the 50-year-old, etc.) because everything would have already happened, everything has always happened that way. In your head, it feels like they are “cycles”, because you’d get to the party and would see it happen again and again – and yet it’s not an event “repeating” itself over and over, but a single event, a single point in the circle. It must feel weird: the 80-year-old “you” will see your 20-year-old you and think, “damn, (s)he’ll be alive after I’m dead – so (s)he’ll be here to repeat all of this!”. In a certain sense, yes, your worldline will go several times through the same point in time, which is crucial. In this limited sense, there are cycles: your worldline just “passes by” the party, then after that it goes through another path before passing by it again. But this is just the way we experience time; your 20-year-old “you” wouldn’t be able to also be 80 years old to experience these two perspectives simultaneously. You’re not Dr. Manhattan; hence the “presentism” of common sense, according to which only the “present” is real; according to which each time you arrived the party would be recreated from scratch, undetermined. However, eternalist determinism tells us that, objectively, no version of you could “change” anything in the party, and that, subjectively, each version of you is there for the first time, because you are being that version of yourself for the first time. Therefore, it doesn’t make sense to think of “changing” what you’ve done if you’re acting for the first time from the point of view of each “you”.

The show toys with this idea through The Unknown(s)’s actions. Although he (they) was (were) taught by Eva, according to whom Erit Lux’s actions maintain the circle, the combined action of the young, adult and elderly versions of him symbolise the immutability of whatever happens (everywhere they go will look like the “party” I described above). They are inevitable at each step they take. When we watch the show, especially from the beginning, we wonder what will happen “if things are different this time”. The standard response to that is “that’s not possible” (if Mikkel went back to 2019, Jonas couldn’t be born; Jonas can’t die because Adam’s already there, etc.). Although this is another classic paradox of time travel stories, deep down we persist: “Ok, things repeat in cycles. But what about the next time they repeat? The next cycle? Can’t things be different then?“. But there is no “next time”, as each point in time is unique. The “cycles” might exist, but they are completely determined.

Introducing indeterminism

There is only one small problem with this way of understanding Adam’s and Eve’s universes, and it’s called quantum physics (QP)[9] – which is general relativity’s actual, real-world problem. Although large objects, the kind we see everyday, behave in this “deterministic” way (every action has a reaction, Newton’s laws, gravity deforms spacetime in a calculable way, etc.), we don’t see the same behaviour in the realm of the invisible-to-the-eye particles that make up these large objects. An electron, for instance, behaves in two ways: as a particle (like a tennis ball) and as a wave (like the ones the water would make if you threw a tennis ball onto a swimming pool). The video below explains in a very easy way the experiment that allowed us to realise that:

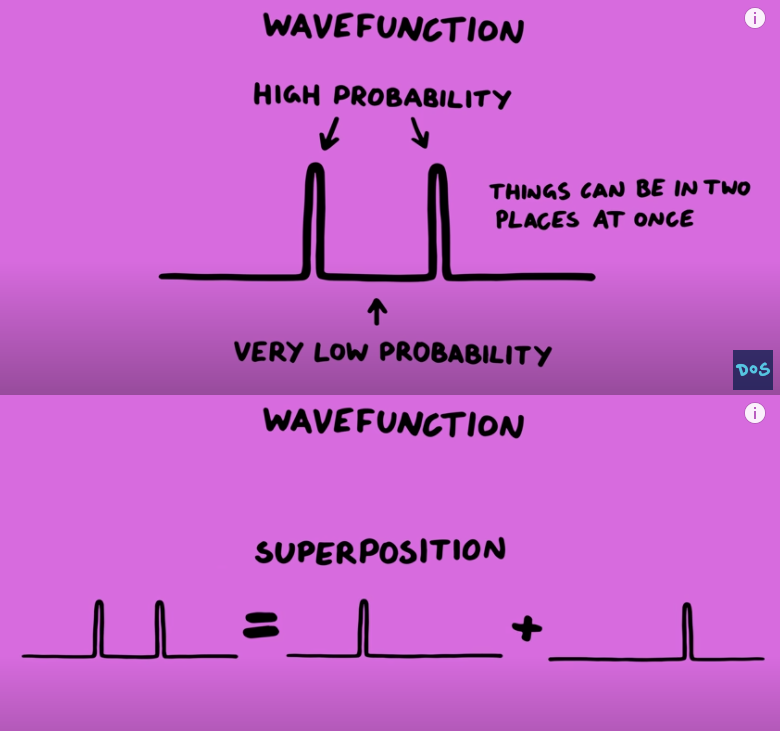

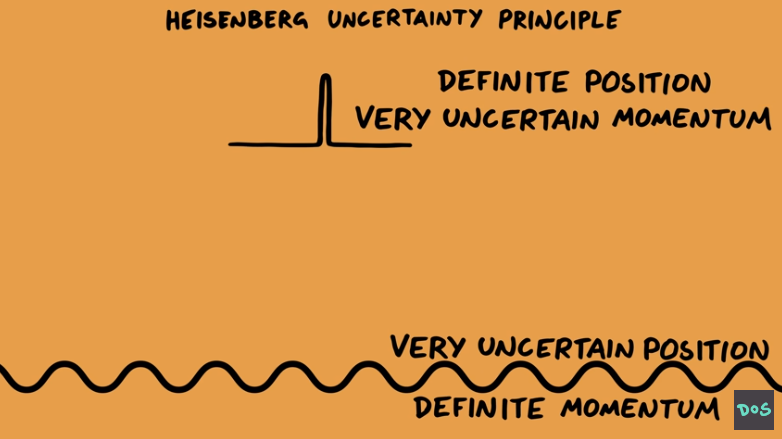

Therefore, every subatomic particle (I’ll use electrons as examples from now on, for brevity) is better represented by a wavefunction, an equation that describes this double behaviour. If you want to know where the electron is as a particle – what’s its position – you can even get that information, but you’ll stop seeing its momentum, that is, its direction, its energy, etc. If you want to know what its momentum is, you’d have to see the electron as a wave, but if you do that, you no longer know where it is exactly – a wave doesn’t exist in a single point in space, right? But why does a wavefunction describe the electron better, if it is a wave and a particle at the same time? Because the electron’s wave hints at a “distribution of probabilities”, that is, the places where there’s greater or lesser chance of it appearing as a particule once its position is determined. This is basically Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, which you may have heard of in high school. You might know something about an electron, but not everything. And, what’s more important, every time you determine one of the things that can be determined, it will be determined randomly.

“Einstein, stop telling God what to do.” – Niels Bohr

This is what irked Einstein so much. The existence of true randomness indicates the impossibility of pure determination from one moment to the next. To Einstein, this meant QP was an incomplete theory. He wasn’t totally wrong; although all the bizarre things the theory says should happen do happen in labs, and make sense mathematically, general relativity is also unavoidable. To reconcile the two theories is a huge challenge, still unfinished in physics – and it involves the controversy of interpreting QP, that is, what these equations and experiments tell us about the nature of reality.

Interpreting quantum physics

The classic interpretation of QP is called the “Copenhagen interpretation“, and it goes like this: the electron behaves like a wave until it is “observed” (measured by a device), moment in which the wave “collapses” in the form of a particle. The wave behaviour implies an important characteristic of QP: the “superposition”. If the electron has superposed positions, it can be at several places at once. If it’s got 50% chance of being here and 50% chance of being there, it’s as if it really were at the two places at the same time, and in experiments it acts as if it really were. According to the Copenhagen perspective, when the electron is observed, the wave “collapses” and it (randomly; probabilistically) reveals itself to be somewhere as a particle.

REMARK 3: For some people, this is just an instrumental problem. “Measuring” something this small inevitably means “interacting” with it. To see something, we need light. Although turning the light on will not make us bounce off a chair, the light itself is made of subatomic particles, and therefore using it to study a particule is like throwing a particle onto another. Any attempt of measuring a particle will, therefore, affect it.

However, things don’t look so simple. Elitzur and Dolev, for instance, argue that the indetermination is ontological, not merely instrumental. Although the issue of “measuring one particule with another” shows we can’t measure the position and the momentum of a particle at the same time, the EPR-Bell experiment seems to indicate that the variables are not only “unknown” before they are measured, but that they don’t exist before being measured.

“I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.” – Richard Feynman

Knowing the idea of superposition, as well as the Copenhagen interpretation, will prove useful later. For now, notice that, according to this perspective, there is no physical explanation for this “collapse” and, honestly, many are unfazed by this: as long as the math works out, it doesn’t matter. By shrugging this off, physics accepts indetermination: where is the electron? I don’t know. We know it might show up here, or there, or over there… But, if we can’t be sure, causes and effects can only exist retroactively, we can’t determine them beforehand. There can’t be determinism. God plays dice; in fact, He does it all the time.

REMARK 4: Critical realism also offers an alternative to a deterministic outlook on the universe, based on the idea of “emerging levels” of complexity. However, I’m not sure about how that relates to quantum randomness.

No, Dark‘s got nothing to do with Many Worlds theory

One of the most popular interpretations of QP (not only among scientists, but among laypeople), is the Many Worlds theory. Time would be a line in constant bifurcation. Each time an electron stops being superposed (every time it probabilistically collapses), the universe splits in two, one for each possible position. Then in each “parallel universe” the electron will have collapsed in a different location; from each one’s perspective, it only collapsed to a single position.

This theory pisses me off because, first of all, it’s not even very scientific (it’s unfalsifiable[10]). You can surely see why it seems useful in the context of Dark – a series with both parallel “universes” and “realities”. However, there are two issues with using it to interpret the show:

- The theory does not seem to propose ways of “going” from one universe to another; in fact, it does the exact opposite. Universes generated from a wave function “collapse” are mutually inaccessible.

- The theory does not say the universe only ever splits in special moments (such as Tannhaus turning his machine on in the original universe), but rather that it does zillions of times at each fraction of a second all over the universe.

The theory’s determinism, being merely retroactive, doesn’t really conflict with the show; at any rate, we shall dismiss it from now on, since it doesn’t help us in any way.

What it’s like to live in Winden

After all that, we are in possession of a technical vocabulary good enough to begin an investigation into the three first questions at the beginning of this section. What is the (internal) nature of Adam’s and Eve’s universes? Can we describe them as deterministic (because they constitute CTCs) or not (as they can’t escape the effects of quantum indetermination)? It seems to me that they are both things: Adam’s and Eve’s universes are “semidetermined”.

Compare Michael’s suicide scenes below (figure 4). Notice how the first time we see it happen, the day is beautiful. The second time around, however, it’s pouring rain.

Although we can’t know for sure how to interpret QP properly in real life, the show’s creative team made it so that the universes created by Tannhaus were non-deterministic – that is, they work in accordance with an interpretation of QP that allows for true randomness. On the other hand, the “circularity” of time demands a consistency of cause and effect that is kept despite these little variations (such as the changing weather). We thus have (in Adam’s and Eve’s universes) a mixture of deterministic eternalism (due to the wormholes causing CTCs) with QP (which provokes indetermination), resulting in points in time in which the same things happen, although with small variations each time worldlines go through them again.

REMARK 5: A gun working or suffering from a tiny defect that makes it “jam” is the sort of thing that we would imagine could be randomly changed by quantum variation. However, in at least two scenes we see guns failing in very convenient ways (since they were fundamental for the story’s consistency). We still don’t know whether they failed due to a more structural cause that is always there each time, or if, despite the quantum variation, some chronological protection is in effect in Adam’s and Eve’s universes. Maybe this protection is a necessary parameter imposed by the operation of Tannhaus’s machine, as we shall see next.

Tannhaus’s plan

To understand how that is possible, let’s talk a bit about how these universes were created. Heinrich Gustav Tannhaus is Winden’s clockmaker. His forefathers believed in the possibility of time travel. In 1986, he concludes a machine in the hopes of avoiding a car accident in 1971 that killed his son, his daughter-in-law, and his granddaughter.

If we assume that Tannhaus’s universe is like ours, time travel is not possible. Even if we believe in determinist eternalism, there are no wormholes on Earth. Besides, as in the lottery example, if in the future it were possible to go back to our past, this would have already happened, and with every cause having a consequence and vice versa, stability would be kept anyway. It is not possible to change what already happened, because whatever happened is already inserted in the chain of causes and consequences, having caused other things that have already happened. Without the car accident, the machine wouldn’t have even been created by Tannhaus in the first place!

Tannhaus, unlike his ancestors, seemed to be very much aware of all this. While planning for his machine (S03E07, emphases added), he comments:

[People] long in vain for a way to turn back time. A way to reverse death. But, if time is relative and nothing is really ever in the past, and the simultaneous overlapping of different realities is possible, shouldn’t it then be possible to bring back something that was believed to be dead long ago and to create a new reality in which what is dead lives again?

We can therefore conclude that Tannhaus, in possession of more knowledge on the laws of physics, didn’t mean to “fool” them; he knew this would be “in vain”. He projected a machine to try and change said rules. However, he soon must have found an obstacle that made him change course (altering the laws would only work “from now on”; or maybe it wouldn’t be possible to change the laws of the universe from within it – something like that). As we discarded the Many Worlds theory above, his goal couldn’t have been to “access a parallel universe”[11]. He must have concluded that his only option was to create a new universe (see quote above), with different laws, in which another version of himself didn’t have to suffer with the death of his family. Obviously, there isn’t a natural law that determines whether a specific car accident happens or not. However, there are some that make travelling through time harder. Therefore, the most promising strategy must have been to create a universe like his own, but one in which time travel is possible – not only theoretically, but in practice, in 1986, in Winden – so that another version of himself could prevent the accident from happening. The accident would be avoided, in this case, in this other universe: his own would have to be destroyed to propel this leap of faith forward.

The effect of Tannhaus’s machine

In the last episode of the show, Claudia explains that the machine “split and destroyed” Tannhaus’s world. She says that he made a “single mistake”, which we can interpret as having built the machine in the first place (it is a mistake from her perspective, that is, someone doomed to witness – and make – her daughter suffer and die). Notice that she never says that Tannhaus wanted to “turn back time”, which reinforces (or at least doesn’t contradict) the notion that he wanted to created a new universe. Therefore, he didn’t make a mistake in the sense that, had he made better calculations, his universe wouldn’t have been destroyed. He seems (S03E07, emphasis added) to know the implications of his act:

All the paths we take in our lives, every decision that we make, is guided by that which we desire deep inside ourselves. We cannot fight that desire. It determines every one of our deeds, no matter how grave and unimaginable they seem.

The false vacuum of the Higgs Boson might explain the destruction of the universe. It makes sense that the Higgs Boson (the subatomic element that allows matter to have mass) relates to how the machine works because 1) the machine involves creating a universe (which will need mass), and 2) interacting with the mass of the whole current universe might be needed for the new universe to look like the current one[12]. The Higgs Boson is also at times (stupidly) called “the God particle”, and if the show uses this element in a particularly fictitious manner, there could be an “internal” explanation for that: the machine’s purpose is precisely to change the rules of physics, and therefore the universes we see in the show (Adam’s and Eve’s) literally work according to different laws of physics; geometries that induce trajectories such as CTCs, deeply altering their chain of causality.

Tannhaus’s machine’s (possible) internal logic

But if he only ever needed one new universe, why were two (Adam’s and Eve’s) created? Why not only one? Why not more than two?

Think about the complexity of the task at hand. The physical parameters of the new universe, we can guess, were already determined by Tannhaus (that wormholes work in such a way, that radioactive waste is such and such, etc.). There are also more direct others (like the fact that time travelling must be possible in Winden in 1986), which likely weren’t many. But this is only the beginning. One must balance the consequences of the universe being this different, above all the projected effects of the CTCs which result from these parameters. Once the possibility of time travelling is open, things can quickly spin out of control. If a radioactive accident is needed to enable time travelling, this already changes the past, as either radioactive waste from somewhere else would have to be taken to Winden for some reason, or it would have to be created in Winden itself (the machine went with the second option: the events led to the opening of a nuclear plant in the town). More changes are needed: Doppler will know about the accident; then Claudia, then Aleksander, and so on. More! If the cave[13] is a passage that goes 33 years to the past and 33 years to the future, someone can enter it in 1978 and leave in 2001 (because in 2001 it already exists, therefore in 1978 it must also exist).

Each of these differences creates an inconsistency of cause and effect that the machine must correct so that the “circle” is closed. For the universes to even be capable of existing, the chains of cause and effect must be stable, despite small quantum variations, incalculable beforehand. The machine cannot create a universe with errors in the chain of causality and just make things up as it goes along, in the hopes that things eventually make sense – or at least we can assume Tannhaus would not bet the destiny of his own world against a machine that didn’t “check” the causal chain of a new universe before “activating” it. On the Wikipedia article on CTCs, we read that their existence “place[s] restrictions on physically allowable states of matter-energy fields in the universe”, meaning not every state of affairs can come to pass, because anything that is done must “eventually result in the state that is identical to the original one”. The universe can only exist when the machine “calculates” every moment so that they are minimally consistent among themselves.

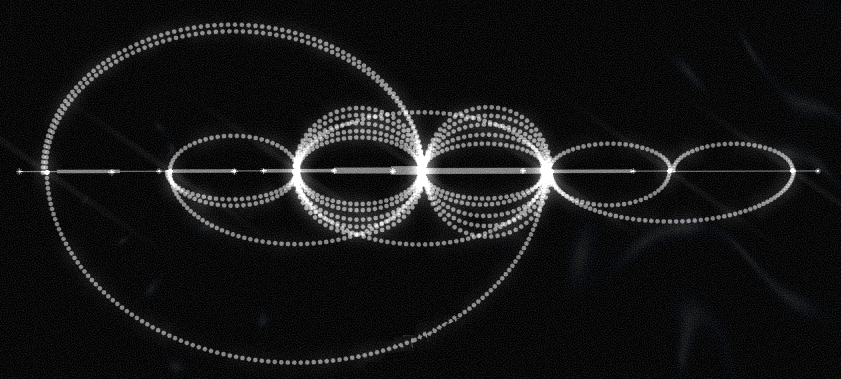

That’s why there must not be many possible universes that satisfy Tannhaus’s parameters. Maybe two is the biggest number the machine hit. Maybe Tannhaus didn’t even have time to choose between the two possibilities – or, since the two universes are together and mutually influence each other (they are “entangled” – we’ll get there), they needed to be created the way they were to satisfy the parameters. Obviously, the attempt to explain what happened in scientific terms bumps into the most fantastical element, Tannhaus’s machine itself. However, if we could fathom a machine with such capacity in real life – creating universes from mathematical formulae – we might imagine that it created two universes because the formula produced two possible trends, like in a logistic map:

Just as with the equation in the video above, picture a formula prepared by Tannhaus in which each successive result would be like the “chain of events” of the universe to be created. It might have happened that, instead of a single trend, the machine generated a balance between two trends: a story such as the one in Eve’s world, and another like the one in Adam’s. In fact, universes are dynamic systems – the most complex ones, evidently – and if a formula could describe them, it would perhaps contain attractors, the “set of numerical values toward which a system tends to evolve, for a wide variety of starting conditions of the system.”

Attractors are extremely relevant in our analysis of Dark. Since they involve CTCs, Adam’s and Eve’s universes occur in “cycles”; hence, it doesn’t matter much if we follow a worldline in 1986 or in 2019, it ends up evolving toward specific behaviours, right? The Wikipedia page for attractors almost reads as inspiration for the show’s creative team: “system values that get close enough to the attractor values remain close even if slightly disturbed”. This explains perfectly the idea of a semidetermined universe: a chaotic formula (like the logistic map’s) gives birth to universes “locally unstable yet globally stable”; there are a few variations (such as quantum ones), but they are not capable of creating big enough differences in the paths that were predetermined by the initial parameters.

What is the “knot”?

The hurdles in creating a universe with worldlines that evolve in consistent chains of cause and effect go way beyond the “inconvenience” of coordinating “events”. It’s not just about “making a nuclear plant be opened in Winden”, but how this happens in terms of human motivation. In the case of the power plant, we know the solution was an intervention by The Unknown, something that in turn needed to be caused, as we know, by the entire tragic story of Jonas and Martha. Anyway, the machine couldn’t simply say “well, and here, after this person travels through time, she’ll decide this isn’t a big deal and will go back to living her life acting as if nothing had happened”. This would never be the case. By the same logic, if maintaining a relationship between two people is making it harder for the circle to be closed, the machine cannot say “the two people will cease to love each other and they will part ways”. If it does that, it must prepare a cause for the dwindling feeling… Which itself requires its own causes! If the machine wants an effect, it must introduce a cause. And if it wants that cause, it needs a cause for that cause, and so on and so forth.

What the show’s characters call the “knot” is nothing more than the “circular” sequence of events (and subjective states) that the machine needed to program based on Tannhaus’s parameters so that the new universes were consistent to the point of existing. The machine has tied the events together, the future to the past, the past to the future, one universe to the other, one reality to the other, in a predetermined way. The machine had to create the worlds this way (planning every moment to preserve the consistency of causes and effects) because if it had made them any other way, they wouldn’t even be.

Jonas (young, adult or Adam) never stood a chance of changing anything, not because he was manipulated by Eva, but because not even Eva could have changed things if she wanted to, as she could not want for anything different. “We are not free in what we do, because we are not free in what we want” means something much more acute in the context of Dark‘s CTCs: Martha/Eva wanted to preserve her child’s life, but her motherly love was just one more planned element in the knot. Other possible universes, in which she wouldn’t want what she wanted, certainly did not make for a consistent chain of events, and hence were not viable for the machine. Her motherly love isn’t the cause of the knot’s continued integrity, even though she certainly thinks it is. As Claudia finds out (a discovery which is also part of the knot), the cause of the knot is external to itself; it’s the operation of Tannhaus’s machine in the original world. Quantum indetermination explains small variations, but these are not enough to substantially alter the trajectory of people’s worldlines, just as QP contradicts determinism without rendering Newton’s laws useless[14].

The particle-universe duality

Knowing how Tannhaus’s machine splits and destroys his universe, we can more confidently move along to the second of the three initial issues: the dynamic of Adam’s and Eve’s universes. If the universe is destroyed due to the activation of the Higgs Boson’s false vacuum, we’d basically be looking at an immense emptiness where before were the machine, Winden, planet Earth… All that is left there, surrounded by nothingness, were two particles resulting from the process for which the machine was made in the first place. Two particles which were probably extremely dense (for they shared the entirety of the original universe’s mass), but particles nonetheless. Inside, the dynamics of each one is each semidetermined spacetime as we see on the show (Adam’s and Eve’s worlds); outside, their interaction is that of two particles in the vacuum.

Just as in QP the fact that subatomic elements behave in two ways is called a “wave-particle duality”, we can call this model the “particle-universe duality”. This is useful because if we imagine that the two universes are linked this way, we can explain three of their most amazing characteristics:

- The profound connectedness in their stories;

- the existence of “parallel realities” in their worldline trajectories; and

- how “time stopping” is related to “two things happening at the same time”.

Entangled universes

“Quantum entanglement” occurs when a subatomic particle interacts with another in specific ways and the two become linked. The definition of entanglement that I found to be most connected to Dark, and which also happens to be the simplest, comes from this website:

A pair or group of particles is entangled when the quantum state of each particle cannot be described independently of the quantum state of the other particle(s).

Therefore, although Eva uses the term in a way that’s a little strange (we don’t know exactly what she’s referring to), we can still read what she says in a way that’s consistent with this theory: the two universes are entangled (having interacted, as particles, the moment the machine made them) in a way that what happens to one cannot be described independently of what happens to the other.

Two superpositions

It is essential to understand that quantum superposition cannot be thought of as merely “being in two places at once”. Read the following explanation by German theoretical physicist Sabine Hossenfelder (emphasis added):

What you think of as a quantum superposition depends on what you want to measure. A state might be a superposition for one measurement, but not for another. Indeed the whole expression “quantum superposition” is entirely meaningless without saying what is being superposed. A photon can be in a superposition of many different positions, and yet not be in a superposition of momenta.

In QP, the moment an element ceases to be in superposition and acquires well defined parameters is called “decoherence” . In general, it is presumed that the constant interaction (with the environment; with one another) between the elements in real life naturally provokes decoherence (watch the video below, starting at 1:52). However, remember that Adam’s and Eve’s particle-universes are, in the context of the original universe, adrift, in the complete emptiness left by the Higgs Boson’s false vacuum-induced destruction. In other words, without any external interaction, the entangled particle-universes can remain coherently superposed over time.

Connect that to Sabine’s explanation of superposition and we have an elegant, simple way to explain “parallel realities”: they are the byproduct of the superposition of each universe. Sometimes, there’s superposition of place (being at two places at the same time): the Jonas who goes to Eve’s world, and the Jonas who become Adam; the Martha who brings him to Eve’s world, and the one who comes back to become Eva. But when the apocalypse “stops time for a fraction of a second”, there’s a superposition of momenta (being at the same place, but going in two diverse directions): the Martha who saves Jonas is at the same place as the Martha who doesn’t save him; it’s the same Martha. But she manages to do two different things.

Further ahead, as we read into Dark‘s events through this perspective, we’ll see how this alters the way we understand what happened in the show. For now, it is important to observe that time “stopping” during the apocalypse does not cause an indetermination, a moment of randomness, a moment in which anything can happen (“Zac Efron”), but rather constitutes itself as an intrinsec feature of the universes, necessary for the circle of causes and consequences to loop perfectly. As Hypnosifl writes on Stack Exchange, “we don’t really know the timeline can be ‘changed’, we only know it is possible to split the timeline into two different versions of events […], but that split could itself be part of the unchanging 4D structure of interacting timelines that is ‘the knot'”. How is it that two (or more) parallel realities could come from a single one? They couldn’t, because there can not be two or more consequences for a single cause without an imbalance in the chain of causes and effects that the machine took so much effort to balance. By the way, even by Eve’s own metaphor things don’t work like that! When she draws the “infinity symbol” with her finger and explains what’s going on, there’s no “bifurcation” in time. The timeline is the same, and it is circular (it loops), running from “inside” or “outside”.

Therefore, unlike what Claudia says, nothing can “change”. The beginning is the end. The parallel realities are not “generated” because they have existed “forever” – or, that is, since the universes were generated as particles that maintain coherence in the vacuum of the destroyed original universe. The machine had to take this into consideration when calculating the chain of causes and consequences. There aren’t millions of Jonas and Marthas, only a handful of them (we shall soon discuss the exact quantity), because there aren’t any other causes that could interfere, in each apocalypse, to generate more realities beyond the two that already exist: if there were, they would have already occurred. You can’t even say there would be millions of Jonas and Marthas if the cycles could continue repeating themselves, because a single “cycle” would have never happened if the others had not also already happened. The quantum properties of Adam’s and Eve’s universes, as particles, explain the superposition of realities, but those same properties of the universes as universes are not capable of causing, from the fact of superposition, changes in these dynamic systems whose paths were determined by the attractors in Tannhaus’ machine’s formula.

The show’s selling a red herring. The clue to the fact that everything happens as it always has is in the fact that little Jonas and child Martha had already seen their slightly older selves in the “corridor” between the three worlds. The showrunners didn’t trade self-consistency for lame drama; that was a wink to the audience, indicating that just as in one reality the “knot” is kept, in the other, it is broken – and the two need each other, they maintain one another, as we shall see below.

The paradox in what we’re told about the ending

Having understood the way Tannhaus’s machine created both universes and how it determined their internal dynamics, we can comprehend what really took place at the end of Dark. Here, two interpretations are possible. This is the case because although CTCs impose an “eternalist” logic to Adam’s and Eve’s universes, we don’t know what the original universe’s laws are like. Since we can assume they’re as complex as ours (relativity and QP should work together, we just don’t know how), at least two interpretations, based on different (non-deterministic) interpretations of QP, are possible.

Let’s begin by what Dark shows us: Jonas and Martha prevent the accident from happening. Without the accident, Tannhaus never builds a machine. Without the machine, his universes were never created. As the universes never existed, Martha and Jonas also cease to exist.

The problem is in the necessary continuation of the paragraph above. Since Martha’s and Jonas’s universes never existed, Martha and Jonas didn’t either. But, if they never existed, Martha and Jonas could have never prevented the accident. If they could not have prevented the accident, the accident happens and the time machine exists… Making it so that Martha and Jonas exist. And so that they prevent the accident. And so on and so forth. As pointed out there in the beginning, the accident has to happen so that it can be avoided, and therefore if it is avoided, it cannot be avoided. Paradoxes exist in Adam’s and Eve’s universes, such as Bootstrap’s; but, as we saw above, we can understand that these universes were created precisely to accommodate for the consequences of time travelling, so that’s fine. There’s an outside cause for the paradoxical circle of causation. We’re talking about a falsidical paradox, not an antinomy. But in the case of the ending, there’s no explanation. We can only justify that the original universe can handle paradoxes if we imagine[15] that it too is different from ours. But we don’t actually need this to explain what really happened.

The Copenhagen ending

“I’m sick and tired of this block universe… I don’t think that next Thursday has the same footing as this Thursday. The future does not exist. It does not! Ontologically, it’s not there.” – Avshalom Elitzur

If quantum variation and the absence of CTCs make it likely that the original universe is not eternalist, let us suppose, for the sake of this interpretation of the show’s ending, that it is a growing block. Let us also adjust the growing block theory to accomodate for general relativity: the present of each worldline exists, as well as its past – but not its future. Therefore, this universe’s past (up until 1986) remains “conserved”, so to speak, and so it can be accessed by Jonas and Martha.

However, in this interpretation, Jonas and Martha don’t literally go to the past of the original universe. After all, time travel only works within their universes, not outside of them; it required their universes’ laws of physics. Tannhaus created these universes exactly because he could not travel back in time in his universe. So, Jonas and Martha would not have been able to, in the original universe, use the Orb (figure 7 above) to go to 1971. I propose, then, that they went to the point in time when the original universe “connects” with both particle-universes (1986) to “gather data” on the original universe – or “gather energy”, as I shall detail below. In this scenario, Jonas and Martha recreate the original universe, beginning in 1971.

Jonas and Martha do not tip us off that that’s what they’re doing, but they wouldn’t need to know that for the plan to work: the operation could be built into the Orb (not Jonas nor Martha know anything[16] about that machine, after all). Hence they might have had to return to 1986 just to have access to the original universe’s “moulds”, with the orb ready to use them. It makes sense that everything that’s “left” of the original, destroyed universe is present in the moment Adam’s and Eve’s universes were created, like a “fingerprint” of, at least, the events that led to the construction of Tannhaus’s machine. On the other hand, it is also possible that Claudia has discovered the parameters necessary to recreate it, the same way she found out it existed in the first place, and then just left it preset to create an universe in which time travel is not possible, so that everyone whose existence was owed to this possibility would not be there. In this case, the trip to 1986 to create such a universe was needed due to the energy requirements of such task: the Orb works well for “trips” between already-present universes with its limited fuel, but would take much more energy to create a universe. Hence the need to take advantage of the nuclear accidents. It is even possible to combine the two explanations into one. The original universe’s past, somehow conserved in 1986, as well as the energy liberated in the use of the original machine, are both used by the Orb to create a new universe, with new parameters.

In any case, I’m assuming the Orb can create universes because it can at the same time travel through time and between universes. As Adam’s and Eve’s universes (across which the Orb allows one to go) are particles created from a mathematical process by Tannhaus’s machine, we can assume that going from one to the other somehow requires “discovering” that formula. This kind of interaction might as well imply the capacity to produce a new formula – not merely interact with the one that’s already there. What I am trying to say is that the Orb, as a kind of improved version of Tannhaus’s original machine, can also create universes with different natural laws. Therefore, Martha and Jonas did not visit the past of a universe that already existed; that universe needed to remain the same so that it could have created them in the first place. What they did was to create a new one in the shape of the old (“ctrl+c / ctrl+v”), with the only difference that, in this new one, they prevent the accident they knew was about to happen.

But why would Jonas’s and Martha’s worlds disappear after the creation of this new universe? Well, because now there’s a whole other universe for the two entangled “particles” to interact with. The creation of a new universe forces a “decoherence”, that is, the end of their superpositions. Schrödinger’s cat is alive and dead at the same time (with its realities superposed) only as long as it’s not “observed”. Finally being outside the knot, Jonas and Martha can “observe” the built universes; observed, the parallel realities collapse onto one another (just like the wave collapses into a particle). As the parallel realities collapse, just as an electron must “decide” where it will show up, there can not be several Marthas and various Jonas, only one of each. Without that superposition, the causes and effects that have supported the history of the entangled universes disintegrate, since their consistency required the existence of these different versions of these people. That is why the two worlds fall apart, with only the new one left standing.

The Advanced Action ending

However, there’s another interpretation of QP that applies to our world, and therefore possibly to Tannhaus’s original one as well. This interpretation is called the Advanced Action [AA] hypothesis, and it is described in this article by Avshalom Elitzur and Shahar Dolev, based on experiments and in other interpretations of QP (such as the Transactional Interpretation posited by physicist and sci-fi author John Cramer). We’ll need to talk a little about the AA hypothesis to understand how this throws new light over the ending of Dark.

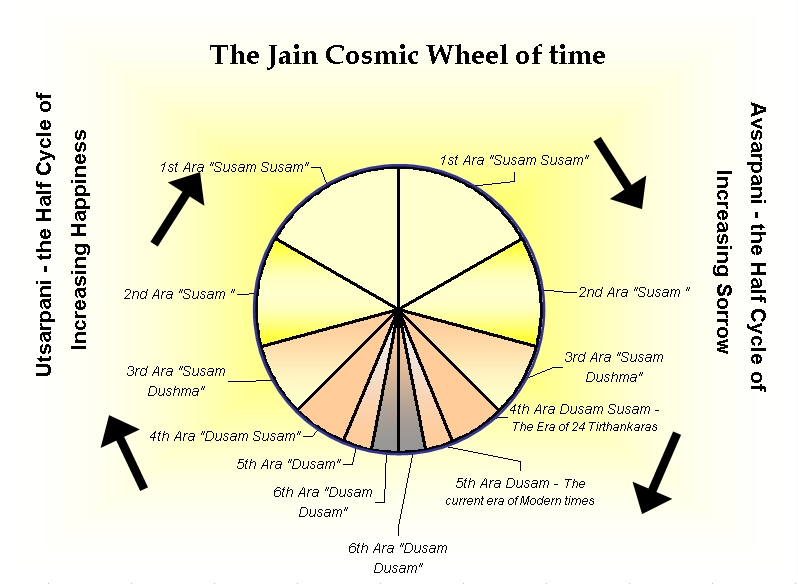

In their article, Elitzur and Dolev explain that it’s not actually true that there’s nothing in the universe preventing worldlines from going toward the past, as we saw there in the beginning of the text. They call attention to the second law of thermodynamics, which says that the quantity of entropy (variation or disorder in a system) always tends to increase. The eternalist reply is that this is all a matter of “initial conditions”. Since the universe is the result of an explosion, that is, everything that was well and good, packed up tightly, started to expand, we could just as well imagine an initial condition in which everything begins disorderly and ends up nice and tidy in a single spot. This is therefore a symmetrical, reversible notion of time. Elitzur and Dolev argue, however, that it doesn’t work quite like that (see figure 8 above); and if time is an asymmetric property of the universe, then QP would validate the growing block theory as much as general relativity would validate the universal block. According to the authors:

This argument for time asymmetry reopens the issue of time transience. If determinism does not hold, then […] physics can no longer boast the consistency between denying time transience and dismissing time asymmetry[…] in the absence of a proof for determinism, we have no reason to believe that the future “already” exists, causally determining the universe’s present and past. The person-in-the-street picture of Becoming, in which the future is ontologically inexistent, to be genuinely created anew, regains credibility.

What they propose is that the past not only exists in each moment that the present ceases to be the present (growing block), but that it can be retroactively modified by the present. In the interpretation of QP according to the AA hypothesis (still according to Elitzur and Dolev), “any quantum interaction is brought about not by one wave function but by the combined effect of two (or even more) waves, going back and forth in time. The initial wave goes from the source to the future absorber(s), such as measuring device, observer, etc. (one or more), while the reciprocal, “advanced”, waves(s) return to the source backwards in time”. In the article, the authors cite experiments in which the only possible conclusion is that “measurement affects not only the system’s present state but its entire history”, that is, “the Quantum Interaction Involves ‘Rewriting’ of the Evolution in Spacetime”.

Now it’s easy to understand what may have happened in the ending of Dark if we assume that this interpretation of QP is correct, that is, that it is valid for the original universe, in whose emptiness both particle-universes interact “quantumly”. The result of the interaction in which the knot is formed and kept (initial wave) is the production of an “advanced wave” in which Jonas and Martha destroy the knot that rewrites the history of the universe in order to avoid the 1971 accident. The antinomy of the ending as we know it also becomes a falsidical paradox, because now there’s an explanation. Yes, the accident must happen in order to be avoided, because reality itself is made of various interactions which, on a quantum level, can “correct” their trajectories in the past. Just as in almost all science referenced in Dark, this is a huge exaggeration; as Marshall Barnes says, CTCs are time machines as much as waterfalls are washing machines. Experiments in which the past is “rewritten” must not have lasted longer than a few seconds, and here we are asked to think that quantum interactions could rewrite over a decade of universal history. Even then, if this is what the creative team was thinking of, it’s all about a poetic reading of a promising contemporary interpretation of quantum physics.

Reinterpreting the events

With the theory above, we can more precisely navigate Dark‘s mysteries. We know what Tannhaus’s machine did, the nature of Adam’s and Eve’s universes, and the possible ways in which their dynamics (depending on how we interpret the physics of Tannhaus’s original universe) lead to the ending we see on screen, even if both possibilities assume the show “lies” a little to the audience. This “lie” is, therefore, the first thing we should understand: why Claudia tells Adam that things can “change”, even when that’s not exactly what happens? After that, we’ll see what other things the show might have “hidden” from us, especially considering that the parallel realities were not “generated” at the apocalypse but, on the contrary, have always existed, as an effect of the quantum superposition of the two universes.

Claudia’s strategic choice

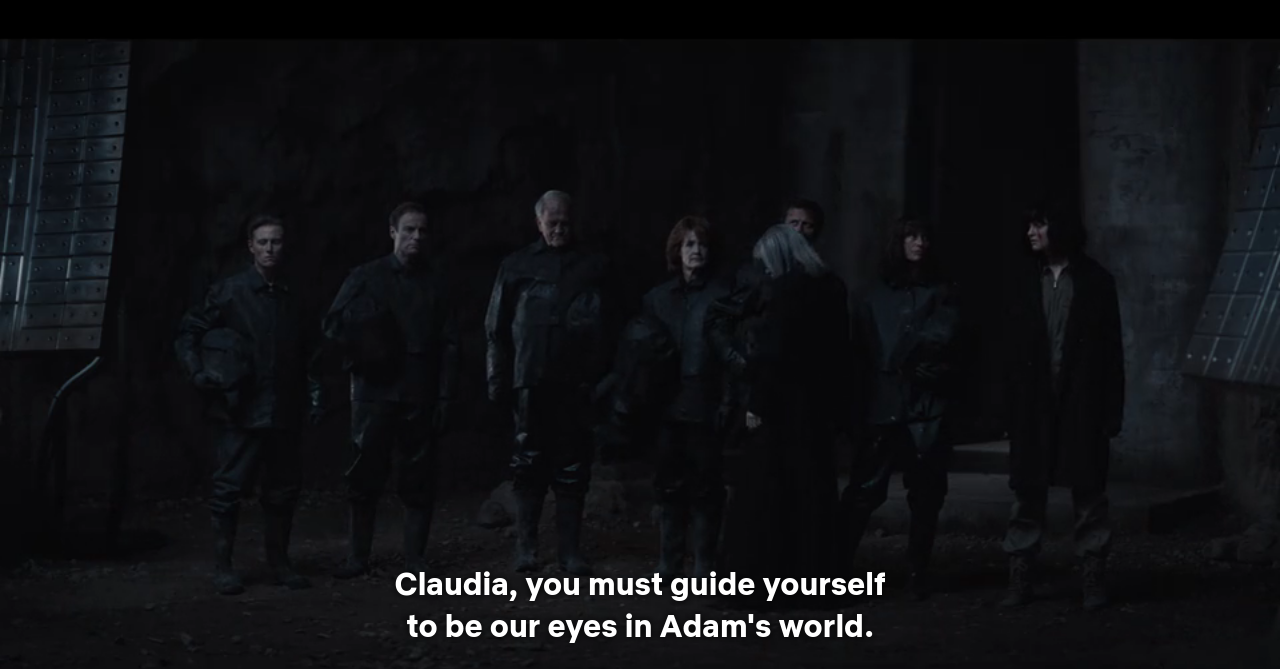

In episode S03E08, Claudia says the following to Adam:

You trying to destroy the origin, that has happened an infinite number of times. But this here, you and I, is happening for the first time.

However, Claudia very likely knows this isn’t the case. Right after this conversation, she talks to a younger version of herself (maybe even a duplicate version, as I shall argue in a minute) and goes away to do all the things we saw her do in the second season – some of which she even knows she has done (like bury the time machine for herself). It is possible that she thinks that, in other “cycles”, she has done all that she’s done after the conversation with Adam without the conversation having taken place (especially if it was with a duplicate version of herself that she talked with after talking to Adam). However, there aren’t many reasons[17] to assume that. At any rate, we either “believe” the show in the sense of taking for granted what the characters tell us, without thinking that they can be deceiving themselves, others, or both, or we “believe” that the show was made with such attention to detail that something else must be going on. As you may have already noticed, maybe running the risk of giving a Netflix show too much credit, I’m betting on the second option here. To me, the worlds of Adam and Eva are repetitions[18] (with slight variations) of everything that happens, including the moment in which Jonas and Martha destroy the universes. The question is if Claudia knows that too, and hence lied to Adam, or if she’s as deluded as he is.

We’ll come back to that in a moment; in any case, there’s at least one very important strategic reason for what Claudia did. The “presentist” illusion, as discussed above, is really strong; even Jonas, who talks a big game of “God is time” and “the beginning is the end” and all else, still seems to cling to an instrumental view of the circular reality, according to which he is the one causing the circularity of time, when in truth we know he’s a part of something much bigger, determined beyond his will. The image that Jonas makes of himself as a (potentially, at least) “cause of events”, is the thread of sanity by which he hangs; the promise to “make it right” has carried him into adulthood, and the one to “destroy everything” has led him, through hatred, to his final atrocities. Fixing, destroying; in both cases, he needs to feel like he’s an active force in the world. When Claudia and Adam talk, therefore, Jonas once again (possibly when it mattered the most) sees that self-image shatter before his eyes.

The issue is that Claudia knows it. She has manipulated everyone, but mainly Jonas, for over three decades by then. She therefore knows that it wouldn’t have been possible to get him to do anything if she’d said “this is part of the knot and therefore has to happen”. When Martha sends adult Jonas into the first season’s missions, she asks him to never lose hope. By making him believe he’s doing something unforetold, she acts by the same instinct, giving him the motivation that she knows he needs to be able to act.

Understanding the parallel realities

However, it would of course be easier to believe that Claudia (and thus, the show) is telling the truth. Can we prove, from what is seen on screen, that nothing new happened? I’ve already cited above the matter of the young Jonas and Martha who see their own older selves going to undo the knot. But how can we prove that each reality is determined by decisions and events within the logic of the connection between universes and realities? By demonstrating that the “circle” closes not only in relation to time, but also to the parallel realities, whose central points of connection are the apocalypses. One reality causes the other, and vice-versa, in a way that leaves no loose ends.

Even in a CTC, the idea of parallel realities as “having always existed” is easier to understand through the very metaphor used by the show[19]. In other words: it is enough to imagine running along the (circular) line of time “on the inside” or “on the outside” (the simple circle on the left of figure 9 below). It’s still a single timeline, but representing “distinct realities” in terms of perspective as well as of acting. Since they never interact, we can imagine events happening differently in each reality without affecting the other. Also notice that the “infinity symbol” used by Eva to explain quantum entanglement (figure 6 above) could still be the “shape” of the “timeline” without an issue, as it would keep each reality apart: the red and blue routes in the “infinity symbol” on the right of figure 9 below are separate sides of the line.

In the apocalypse, as we have seen, causality does not really “break”. It’s all about a superposition of momenta (defined as “points in time”, but also, in the language of physics, as direction and forces). The temporal interruption does not break causes and effects but, on the contrary, creates an abundance of causes and effects. The “circular” nature of the worldline trajectories in the universes is preserved; one reality causes the other as much as the future causes the past. The moment of superposition of momenta is fundamental for “mixing up” the two trajectories, making it so that they can mutually cause each other (in figure 9 above: if this wasn’t a “strange event”, realities could remain completely separated).

REMARK 6: It is necessary to note that quantum superposition – of places and of momenta – is very convenient as a literary device, since the “craziness” of the quantum universe can explain anything. In some moments, there are two versions of Martha around (superposition of places), and the apocalypse forces the division because that’s when two causes act on her, originating two responses (superposition of momenta). After that, there might be other moments like these, according to some logic, as we shall see, but still according to what the story demands, just because… Quantum physics!

At any rate, notice that there aren’t always two versions of everything that happens, only of each event directly impacted by the consequences of the superposition of momenta. For instance: there isn’t a version of the group of 1921 survivors in Adam’s world that was not visited by the Martha who saved Jonas, or that was visited differently; the Martha who did not save Jonas, becoming Eva, “acts in parallel”, but without creating an alternative version of that moment, that remains a single point in time only, consequence of actions from both parallel realities (in this case, the Martha who doesn’t save Jonas needs to become Eva to cause several things that lead to the moment in which the other Martha can save Jonas… And visit the group in 1888).

But wait: if we go back to the “infinity symbol” that Eva uses (figures 6, 9), we see that the moment where the line “meets” itself (representing the apocalypse) does not arrive exactly where we want to – a system in which the line can be ran alternately “on the inside” and “on the outside” consistently, with both sides “mixed up”, permanently connected in the rigid CTC relation of cause and effect we’ve analysed so far. In other words: the symbol that we want is one in which you 1) begin on a specific point, 2) choose a direction, 3) always move straight ahead, 4) follow the rules (switch sides everytime you pass through the superposition of momenta) and 5) end up reaching the point of departure, having ran through all points of both sides of the line. In figure 10 below, we see that this doesn’t happen: each part of the loop is coloured according to the completely segregated realities, based on figure 9 above. There is indeed an “interaction” between both sides, since half of the path the red flow goes through is now on the blue side, and half of the blue flow goes through a route that would otherwise be completely red. However, realities still do not necessarily cause one another. We can therefore conclude that this symbol is as inadequate to understand what happens as Eve’s own comprehension of what is going on in the show.

In what follows we shall review what we know for sure (the events of the show) and some of the things we can presume; then, we’ll do several “informed guesses”, imagining two possible scenarios. Finally, we’ll reach a very familiar symbol that will serve much better to understand how the parallel realities are interlinked in Dark in a way that contemplates all the characteristics of the universes we have seen so far.

Reframing what we see on screen

Pay attention to figure 5 above; if you can, watch the scene again. There is the Martha who enters Jonas’s house to save him, and the other, who returns with Bartosz to Eve’s world. In the first case, however, it is not the case that Martha hears what Bartosz has to say and decides to ignore him. She just… steps into the house. We can thus conclude that this is because Bartosz isn’t there. This is the difference that provokes the pulling of the lever, as indicated by Eva. It does well to also remember that Martha goes to save the Jonas from his apocalypse precisely on the day her own world’s apocalypse is happening, which is another moment when “time stops”. We can assume a very close relation: either Bartosz decides to go talk to Martha, or he doesn’t. The complication here is that his decision must be the consequence of what it causes (Martha either saving Jonas or not): a point of superposition of momenta must lead to another, leading back to the first.

In Eve’s world’s apocalypse, Bartosz may or may not go talk to Martha. This we don’t see on screen, but we can assume that each decision corresponds to what happens in Adam’s world’s apocalypse. At that moment, Martha and Jonas being the only ones directly affected, we see the generation of Martha 1 and Martha 2, as well as of Jonas 1 and Jonas 2 (Bartosz does not duplicate here because this already happened in Eve’s world’s apocalypse). I shall call Martha 1 the one who saves Jonas (and therefore Jonas 1 is the Jonas taken by her to Eve’s world) and Martha 2 the one who comes back with Bartosz and becomes Eva in the future (and therefore Jonas 2 the one who becomes Adam in the future).

We see Jonas 1 getting Martha ‘Zero’ pregnant (I shall use this nomenclature to name every character who hasn’t been “duplicated” yet) and then getting killed by Martha 2, who Eva just began to groom into becoming herself in the future. Martha 1 follows Adam’s orders and ends up killed by him. We then see that, after that, Claudia tells Adam about the original world – and there is something we don’t see, but Eva tells us: Adam ends up killing her, something that the adult version of Martha witnesses (and this is why this Martha remembers it). We can therefore assume that at some point Eva and Adam were also duplicated (Eva 1 and 2; Adam 1 and 2). Finally, Claudia claims to have used an apocalypse to duplicate herself too.

This is really confusing: where’s the other Claudia, then? Was it the one who died? We know that it wasn’t: Dark’s official website confirms what we saw above, i.e. that what she does in the second season (introduce her younger self to the idea of time travelling, ask her father for forgiveness, etc.) was after having talked to Adam. Perhaps it has something to do with the version of her encounter with the adult Claudia in which Gretchen doesn’t show up? How can this “circle” possibly “close”?

What happens at the apocalypse in Eve’s world

“What we know is a drop, what we don’t know is an ocean” – Isaac Newton

Right before the apocalypse in Eve’s world, she sends adult Bartosz to fetch young Bartosz. Eva needs to convince him to retrieve Martha (who will become Martha 2 and, in the future, Eve). It is right when the apocalypse is happening, I assume, that Bartosz must decide whether he’ll do it or not. Present in the room at that moment are young Bartosz, Eva, and Claudia – this one in a specific moment of her learning process.

Why Claudia? We know she found out about what Eva does with Adam’s world’s apocalypse; let’s assume, in this scenario, that it wasn’t long after her first meeting with Eva (the one we saw on screen). We also know that she finds the truth about the original world, although in the beginning details might be missing (for instance, that Tannhaus is to blame). Perhaps still without knowing how or if it is at all possible to access that third world, and certainly seeking answers, experimenting with her unfettered access to all worlds and years (since she’s in possession of the Orb), she might have decided to go through an apocalypse to try to create two versions of herself.

REMARK 7: For more information on the sequence of Claudia’s actions, I recommend this video, even though I disagree with its theories. Therefore, of what “specific moment” of Claudia’s learning process am I talking about? Following the video, we see that in 2040 Claudia kills the version of herself from Eve’s world, learns more about the worlds, travels to 2053 (meeting an older version of herself) and then returns to 2040, growing old alongside Noah and adult Jonas, even if disappearing sometimes to do more research. I think Claudia ought to have “duplicated” herself between the murder of Eve’s world’s Claudia and her trip to 2053 to talk to the version of herself that had just sent Adam to his final destination. This is consistent with the age she displays in the last episode “discovering” the facts on the third universe.

She had already been to Adam’s world’s apocalypse, younger and with Regina – and although that isn’t sufficient reason for her to choose not to go through this one again, she may have preferred to use Eve’s world’s apocalypse because Adam’s one already attracted too much “attention” – after all, this seem to be the only moment Eva finds relevant to her history. Since the younger version of herself from Eva’s world had just been sent (at the same time as adult Bartosz, as we saw on screen) in a mission to make contact with the adult version of herself from Adam’s world, both Claudias (this one who needs to choose an apocalypse to go through and the younger one from Eva’s world) would not meet. This is a small positive for this narrative, as it fits with the idea that the Claudia from Eva’s world had never seen an older version of herself [her Adam’s world self, that is] (S03E07).