I am currently finishing a thesis on the anarchist concept of freedom, so when I came across a book called Dancing & Digging: Proverbs on Freedom & Nature, knowing it was written by someone in the anarchist community broadly conceived, I just had to take a look.

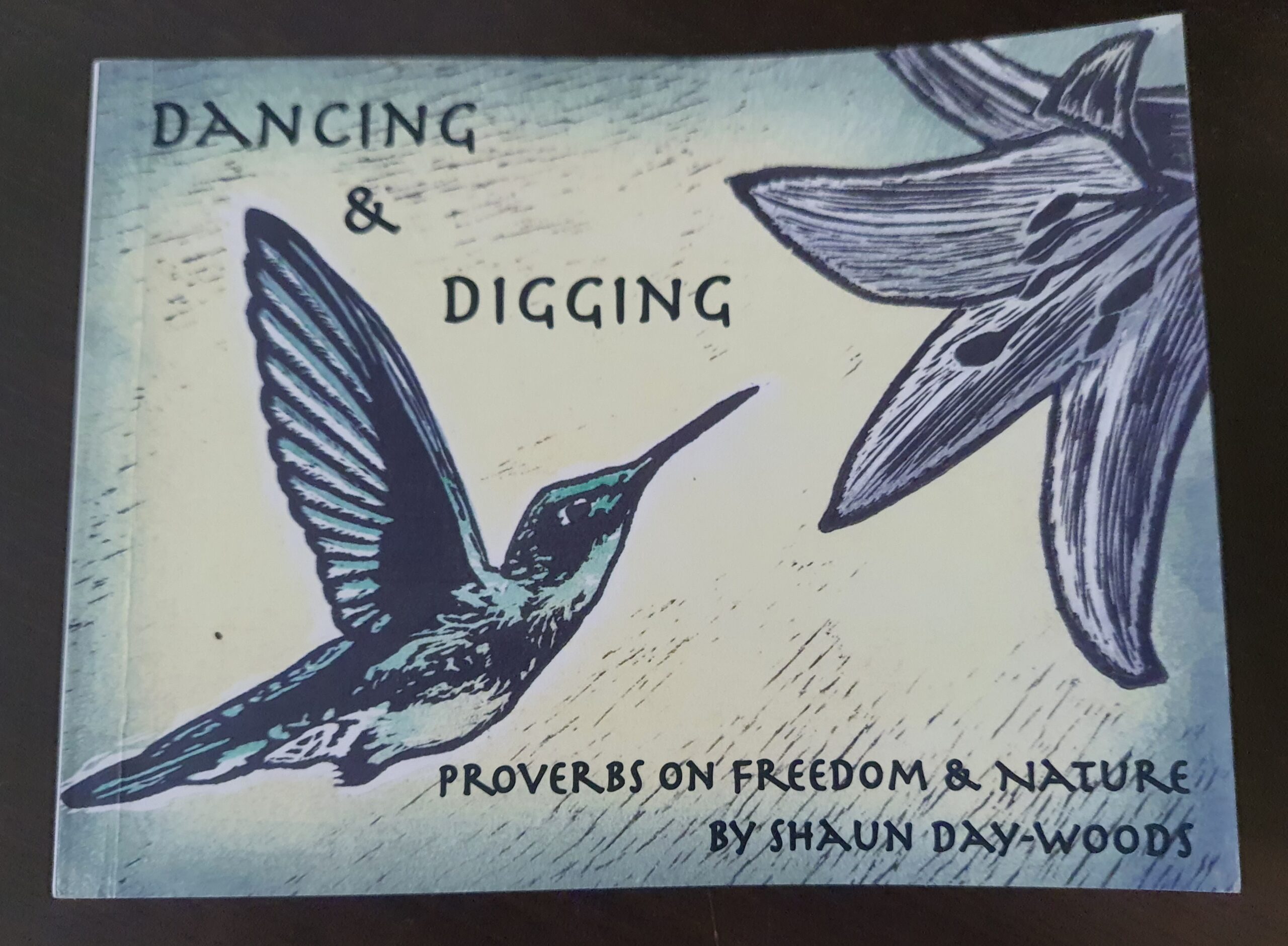

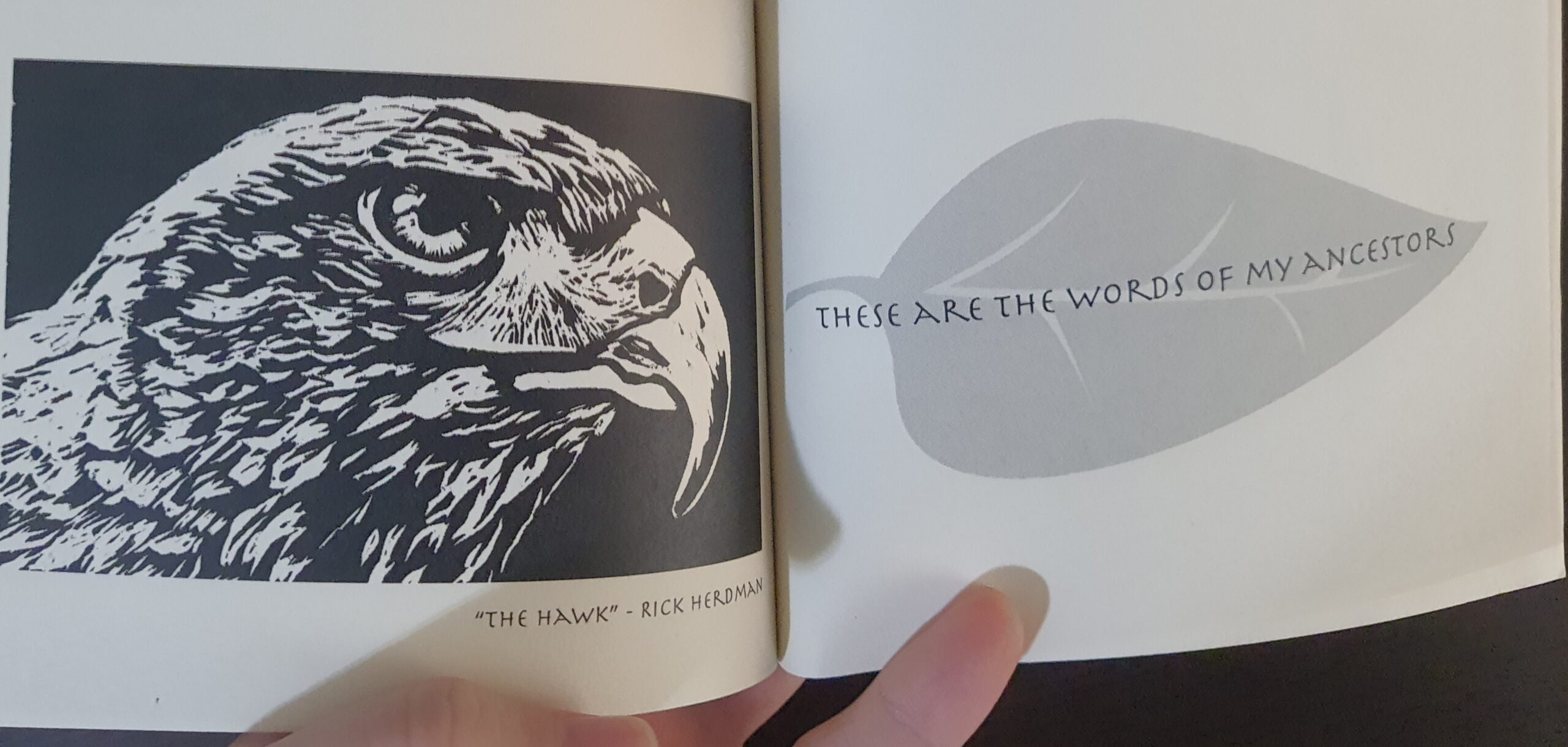

Dancing is a landscape oriented pocket book full of short phrases that encapsulate wisdom regarding, as the author explains, “freedom, nature, surprise, belonging, habitat, anarchy, rebellion, community”, and more. Written by Shaun Day-Woods and also featuring really beautiful woodcuts by Rick Herdman, it was published by Night Forest Press in 2021.

Shape and method

There is very little prose in it; the vast majority of pages are dedicated to housing one or two proverbs each. But the little explanation readers are given is quite insightful. We get a nice definition of proverbs as “the wit of one and the wisdom of many”, and then see them described as phrases that “allow for nuance, layered meanings, humour and irony”, which makes them “ideal to muse over or meditate on”. It is explained that these sentences are “based on [the author’s] lifetime of observations and study as well as on conversations had with friends and neighbours”.

However, it’s unclear whether the book’s “chapters” – such as “These I learned along the way” and “These are the words of my ancestors” – refer literally to the origin of the sayings, since one is more vague (“These came from the wind”) and none of the parts seem to have a particular “personality”. It feels like any proverb could fit anywhere in the book. In any case, most proverbs (in general) have “an untraceable progeny”, and the author writes that although he “might be associated with these for now, the hope is that over time a few will become part of an anonymous radical-folk philosophy”.

Readers are given a recommendation on how to use the book. Basically, there’s no particular order to it (the pages aren’t even numbered) and people shouldn’t binge it. This leads me to a disclaimer about how I used it. I’d love to have taken the leisurely and random approach suggested, but I faced two issues. First, I wanted to be able to cite some proverbs in the thesis. Secondly, I would soon lose access to the book (I bought it with an allowance from my scholarship that requires it to be turned over to the university after I’m done with the write-up). The solution I found was to read two pages (2 to 5 proverbs) every one or two days, sequentially, writing the page number as I counted it on a piece of paper that doubled as a bookmark. Even though I’ll admit this felt a little mechanical, quite unlike the magical promise the book represents, I’m glad I made sure I could read all of it before I had to give it up and that I could cite it properly when needed.

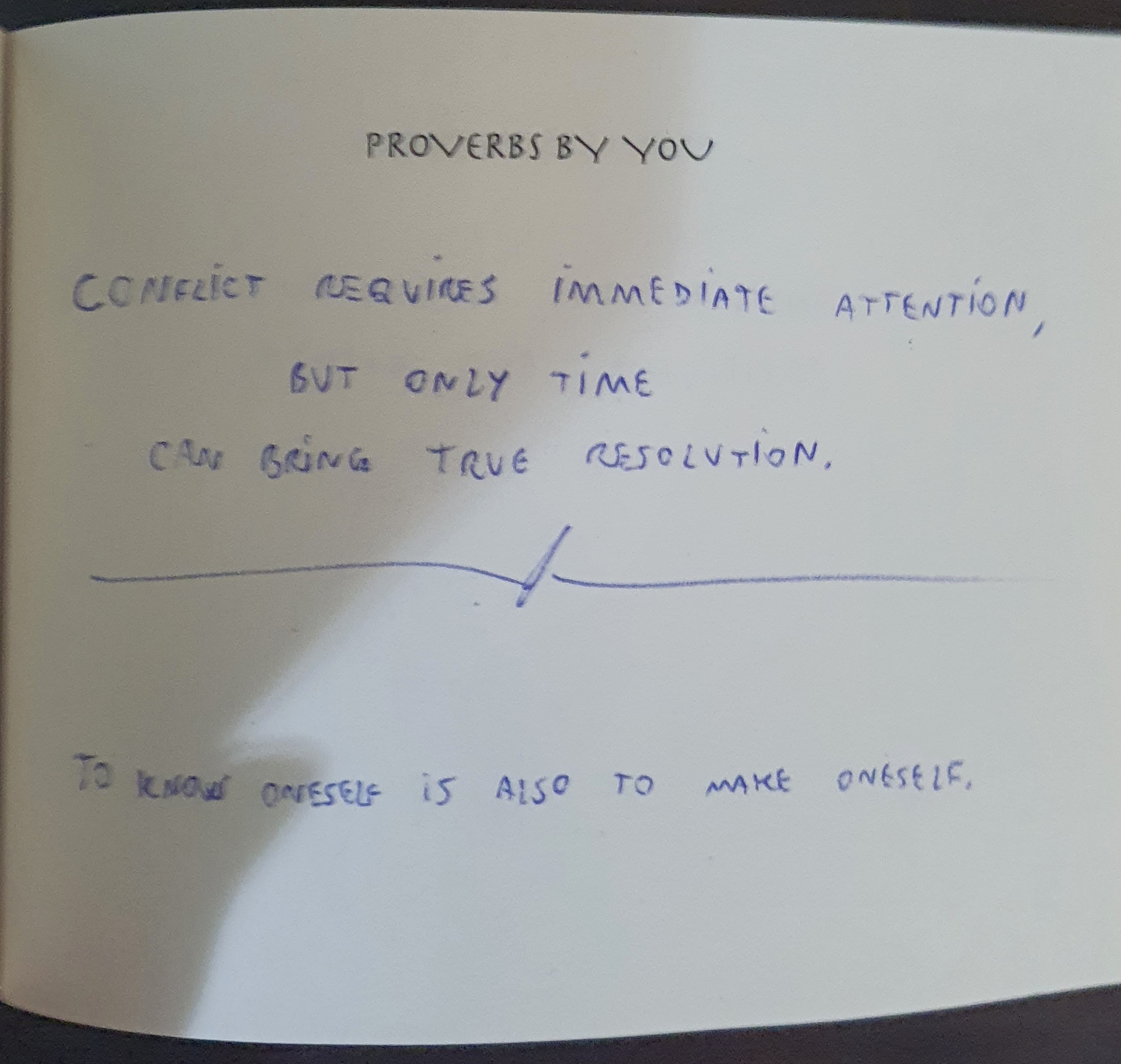

The book is well typeset, with its design perfectly in tune with its content. The format is unusual, and so it immediately sparks curiosity. I wished there were more woodcuts, cause they were just marvelous. There are blank pages at the end, as readers are encouraged to write their own proverbs and share them with the authors, which I thought was a lovely touch. The preface also suggests games to play with the sentences.

On cities

What about the proverbs themselves? I thought at least about a third of them were really good, and for me (as a person even more than as a researcher) they made the book quite worth it. But there were a few things about the rest that irked me in varying degrees.

What first jumps out is a deep hatred for urban landscapes. “Living in a city is living in a dead habitat”; “The city owns the individual”; “Cities arose from negative and harmful forces”; “Hyper-alienation was born in the city”; “Cities are cemeteries” (… because “the wild” is not?), etc. It’s just so relentless that all nuance is lost. I mean, maybe this last one has “layers” – cemeteries are not necessarily bad, right? Well, after reading two dozen variations of “cities are bad”, I doubt it’s not an attack.

Granted, capitalism does shape cities into hellscapes, and so this denunciation is valid. But aren’t proverbs supposed to go beyond current facts to reach for deeper truths? I think there is something charming and genuinely alluring about cities as large gatherings of networked people. What I mean is that it’s legitimate for people to want to “conurbate”, even though I wish we did it in more egalitarian and diverse ways. Cities can surely become better environments overall, also; Kropotkin’s and Reclus’s always struck me as powerful visions for cities.

But criticism here is absolute. “Cities require obedience to authority” – no, no they don’t. They don’t! There’s something about being close to a lot of people that energises us with the prospect of chance encounters, transformations, alternatives, complex collaborations… Something warm and exciting that people should not have to choose over and against “forests”, but neither give up for the sake of those. So even though I can totally see what these proverbs are getting at, the blank condemnation of “the city” as an archetype falls flat on me, and I’m sure it also will on many others.

Shouldn’t I have expected this from a book about nature? Definitely not. I thought it would challenge any rigid boundaries between humans and nature, as anarchists have almost universally done. In fact, a good proverb from the book goes like this: “The fewer the boundaries, the closer to truth”. It could push beyond other dichotomies too, such as life and death. A sentence like “Cities are cemeteries”, by itself, could certainly be a reflection of this last sort – which the book actually does well with other sayings, such as one of my favourites: “You aren’t alive if you aren’t being eaten”. There’s also “After death we decay and become soil nutrients, a final reciprocity with the earth”. And it’s not like the human-nature divide is not challenged either; one of the opening proverbs is “All of nature is inside you”. That, I like. But nuance goes out the window the second cities are mentioned.

I just think we as humans are part of nature and hence everything we do, including cities, is as natural as everything else around us. It might not be good for us, what we’re currently doing with them, but then again nature is about reality itself, encompassing everything, good and bad alike. Maybe I’m thinking about nature, the concept, while the authors just meant it as “trees and rivers and stuff”. It would be a little disappointing, but understandable. Come to think of it, there’s not a lot here about farms… Perhaps they are talking about “wilderness” more specifically.

What does a proverb sound like?

In any case, as the idea of “timelessness” was behind my negative reaction to this city-shaming, I started to ponder on what made a good proverb; perhaps other expectations I had about them could explain what made me dislike other sayings in the book.

For me, proverbs require a “turn-of-phraseness” that includes a certain… pattern? Rhythm? They shouldn’t be too short; “Kill to live” is more like a motto or a slogan. And they definitely should not be very long. The one about “soil nutrients” above could lose the bit after the comma, or collapse it into the first part somehow. Then there’s this: “All around us are invisible veins of existence, streams of life. We need only cup our hands and dip into them to retrieve music, ideas, insights, power”. I’m sorry: this is either a poem, a mini-lecture, or a tweet, but not a proverb.

It also struck me as odd that some sentences were in the imperative mood. What is up with that? Take “Kill to live”, mentioned above. Why not “Everything that lives must kill”, or “To live one must kill”? I don’t know, maybe it’s a Western prejudice that “wisdom” has to do with declarations about reality. But formulas like “X is Y”, “X is not Y, but Z”, “When A, then B”, or “Not every W is C” just seem to fit much more comfortably in that proverb outfit. The imperative mood is even acceptable if it’s a little more complicated; something like a negative conditional (“Don’t X if Y”). Day-Woods is quite clear in the preface that he seeks a more “practical” wisdom, so maybe these instruction-like sayings are coherent in that sense. Regardless; when I read “Become a child” or “Deify your prey”… They just don’t feel like proverbs to me.

What should a proverb do?

Aside from phrasing patterns, there is also the content, and here I had two separate issues: “directness” and the use of “big words”.

I think proverbs stick when they’re not easy. They put you off a little, puzzle you; they are not obvious, even when they’re simple. This involves, for example, playing with angles (“A society with prisons is a prison”), presenting apparent paradoxes (“The more you give the more you have”), or using metaphors (“Don’t turn down the deer unless you have a salmon” – a negative conditional imperative, by the way!).

Some proverbs in the book lacked this; glaringly at times. Take, for example, the classic “An empty mind is the devil’s workshop” (not in the book). The authors seem to disagree, for they’ve given us “An empty mind heals”. Notice the difference? The first one doesn’t go “An empty mind is bad for you”, or “An empty mind harms”. It gives you a mental image to process – a demon cutting plywood. Why not “An empty mind is”… “a hospital”? Maybe these are bad because they are part of the city or something. Fine – “a bandage”? Too simple? “Aloe vera” – medicinal plant, can be found everywhere… Weird sounding? How about this one: “An empty mind is a sage” – a word for both a wise person and a medicinal plant! Another one: “For a broken bone, an empty mind”. It gives pause; surely you want to do something more with the bone to heal it. But while it incorporates the suggestion that empty minds heal, it also says something about cooling down after an aggression or an accident, instead of seeking revenge or feeling guilty.

This is unfortunately a very common problem in this book. “Cities arose from negative and harmful forces”. This is a mini-lecture too, despite its size. “A society with prisons has no greatness” – I much prefer the one above, about it being a prison itself; this one doesn’t leave anything to imagination. It just states what it means! “Music connects hearts”. Yes it does. “Lack of courage dulls life”. Can’t argue with that. “Play is superior to work”. Of course it is!

I mean, they’re not wrong. Maybe I’m not the one who needs to hear them; I’m not a calvinist. It’s just that it doesn’t give the reader the joy and wonder of discovering the meaning through toying around with the words. Or chewing it over time because it’s not clear what it means until you stumble upon an experience that opens it up for you and you finally get it. Critical reflection doesn’t go very far because there’s nowhere to go. “Ah, but you see, one must work to be able to live to able to play, how about that? Gotcha“. But if play is the reward we’re after, it’s still superior. Straightforwardness leads to pedestrian discussions.

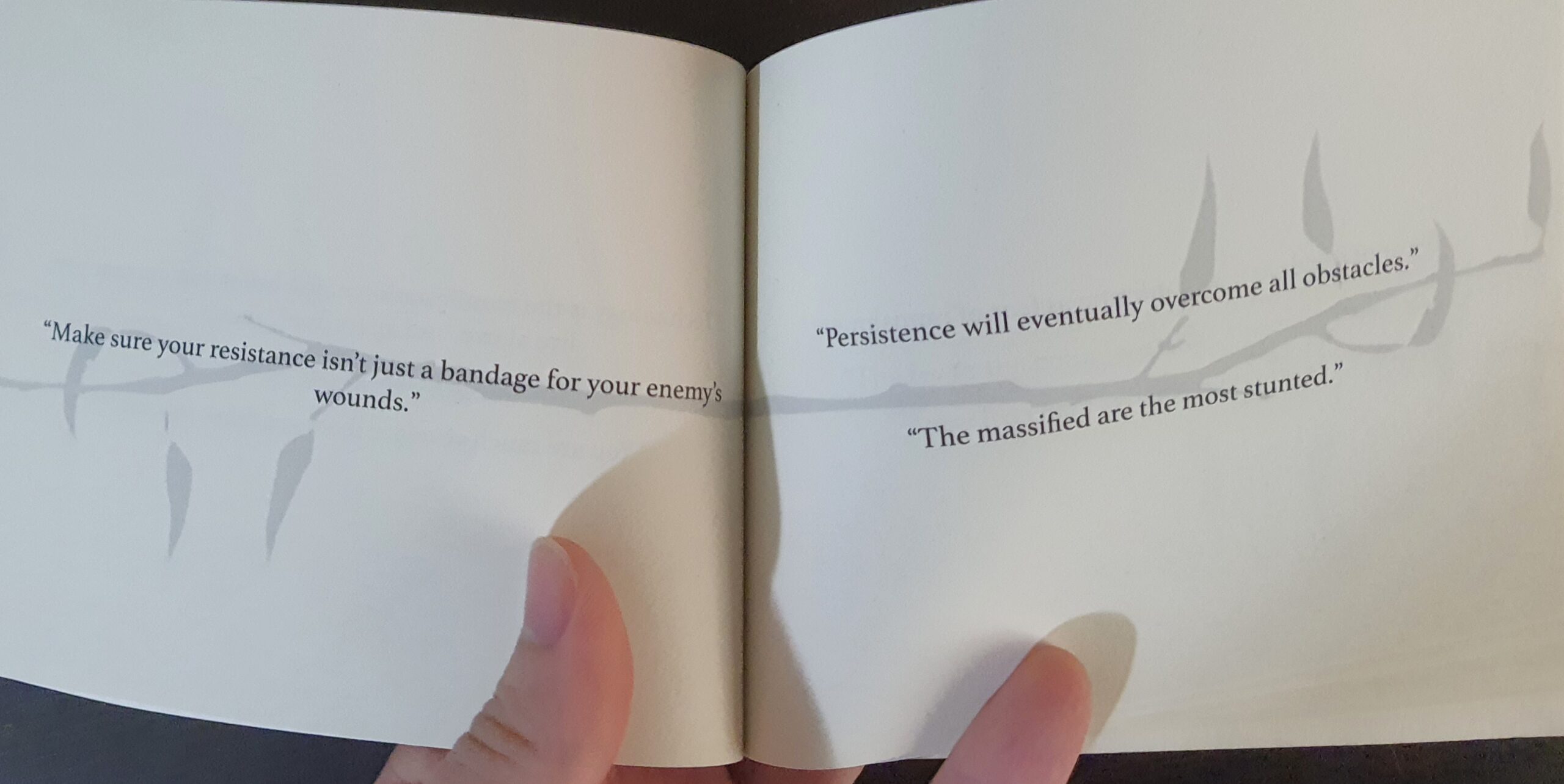

I think the directly political proverbs suffer slightly more from this than others. “Often it is most efficient to make your resistance indirect”. “Understand the difference between attack and defence, or lose”. “Do not let anyone get political power”. “The statist is never on the people’s side”. Are these proverbs or guidelines in a manual for guerrilla warriors? I mean, proverbs can induce us to become a “liberation army” (as one saying goes), and this is a radical book so they really should. But I think they are more effective in this regard if they do so as proverbs; with subtlety, without broadcasting what they are so that they can be planted like seeds on minds behind conservative gates. Funnily enough, I like “Secession is smarter than civil war”, because the macropolitical implications are less interesting than the general principle, which can be applied in many other circumstances. On the other hand, “The cat is patient, but to live must eventually pounce” (right above the “attack and defence” one, by the way) is a good example of wrapping these messages in little disguises. “The currency of banks is the sorrow of exploited humans and the cry of plundered nature”. Why not “Coins are made of tears”? The one in the previous page is more like this: “Our wallets are filled with suffering”.

Let me return to “Play is superior to work”. Why not this: “It’s better to play with a computer than to make one”. Not so fast – there are people who enjoy building computers. This is playful for them! But maybe this refers to the terrible conditions in which the chips and parts themselves are made, or to child slaves in mines and stuff – so considering this, is it good to play with computers at all? We’d still be comparing “play” to “work”, but their complex intertwinement can be teased from the imagery employed. How about this: “I’d rather seesaw than saw”. There is the seesaw (to play with) versus saw, the verb related to using the tool (which can be used to build a seesaw), but there’s also the verb seesaw (as in oscillate, have mood swings) compared to using the tool not for work but for violence. There’s even the revolutionary point, that I don’t think any of these transmit, that we shouldn’t hate “useful activity” itself but make it playful and artistic; we should eliminate drudgery in the “work” needed for everyone’s nourishment and satisfaction.

There are many exceptions here. Indeed there ought to be, since “X + relational verb + Y” is a good shape for proverbs – wouldn’t all of these fall under this criticism? Not really. Take one of my favourites from the book: “Beauty is found, not created”. This is wonderful, because you really resist it at first. Doesn’t it seem odd? Of course it’s created, artists do it all the time! But what are they doing, really? And then you get to thinking… Then you apply it to aesthetic judgments of nature (including people)… Then you return to artists’ processes… Then you think about music – the notes and chords are all there, nothing new is being created; you’re just finding out which go well together. Then you go back to people: are there really ugly people? Or are you just not looking at them with the perspective needed to find the beauty that’s in everyone?

To be fair, “An empty mind heals” can also be resisted (maybe because of the hold the “devil’s workshop” paradigm has on people). I understand that what each proverb in the book has to give depends entirely on the receiving end. Maybe this is absolutely mind-blowing for non-anarchists. But unlike the one about beauty, there’s not a lot to explore about the empty mind’s healing powers. You either accept that as a truth or you deny it. The same goes for “The statist is never on the people’s side”. What about literal populists? Wouldn’t many knee-jerk reject this without a second thought? There’s nothing in the sentence itself that gives you something to work with to help reflect on the issue. There’s no journey. Proverbs should pack a punch and reveal more stuff inside when unpacked. They can be simple, even straighforward, but shouldn’t be a piece of cake nor fall on our ears like a tautology.

Who is a proverb for?

A second problem is the use of big words. Compare, for example, “You aren’t alive if you aren’t being eaten” with “After death we decay and become soil nutrients, a final reciprocity with the earth”. The second one is not only unwieldy, it’s also a bit… Technical? “Decay” has a haunting beauty to it, at least, but “nutrients” and “reciprocity” don’t match its poetic stance. The first, in contrast, uses a basic activity (eating) to explore the hefty concept (being alive), and it makes for a delightful sentence.

The worst offenders here are technical words from the social sciences. “Putting others into a category box is oppression”; “Political power opposes self-creation”. Come on – this could be plucked straight from a text by Foucault, if only he hadn’t been born in France. “Society” is a frequent notion in the book, but what is “a society”? I just don’t believe it’s a useful word for proverbs. I don’t even understand whether the authors think it’s good or bad, since we’re also given phrases like “Societies emerge only when people have lost their connection to nature” and “A group of friends is an intimate, organic circle, not a society”.

I return to timelessness as a criterium. Although there are some modern phenomena discussed that are worth including in sayings, as we can more readily understand them (did I not suggest “computers” above?), there’s something fascinating about reading a proverb about “a village”, because you can extrapolate it to mean something about any “large group” (including cities). On the other hand, modern stuff (prisons, schools) work wonderfully here as symbols for notions that would have otherwise felt like big words – domination, indoctrination, etc.

In the end, I do have to admit timelessness is a little dumb when we’re talking about human affairs, and I came to realise I’m being cranky at this point. There aren’t many more examples of this use of big words, anyway. I guess I initially thought that proverbs should be easily digestible, in terms of the vocabulary used, because if you have to go to the dictionary to understand it, you probably won’t pass it around – you’d be afraid of sounding awfully pedantic. Plus they perform a sort of teaching function, so kids, for instance, should be able to understand them. But then again, it’s important for us to be confused in more than a poetic way, and proverbs could teach people new words, too. There’s nothing wrong with that.

Amidst the recognition that nothing that I’ve written here is a fair appraisal of the book, for every reader will react differently to it, I wish to mount one last defence of my thought process. I guess it all boils down to something like the ability to picture someone saying out loud: “Well, you know what they say! <insert proverb here>”. I swear to you: I cannot imagine someone non-ironically saying “As my grandparents used to say, let ghosts and dogs touch your heart”. I just can’t. It’s not gonna happen. But the criteria above are not absolute. “There is a saying in my family that goes like this: be the first on the dance floor at least once in your life”… Yep. This works.

Let this book touch your heart

In the end, I don’t want to give the impression that these issues are overbearing. In fact – and this is the reason for the disclaimer above – I wonder if I would have even thought about all of this had I not combed down the book’s content at a regular pace. I think engaging so systematically with it made me critical because I liked it; I recognised greatness in the overall idea but thought the execution could be more fine tuned.

There’s a lot to like here; sayings I’ll cherish forever and that I hope I can incorporate into my life. In addition to the ones I already mentioned, here are a few others I really liked: “Don’t die more than once”. “Don’t hide in a maple tree. Autumn always comes”. “Music is the easiest friend one could ever have”. “Enemies can still be our teachers”. “Secure fighters choose their tactic, the weak have it imposed on them”. “The one who calls their opinions theories has colleagues but no friends”. “Facts settle arguments, but they do not solve problems”. “Lack of free time is the greatest poverty”. “Everyone should know what it is to follow, to lead and to walk alone”. “Prisons don’t prevent crime, hospitals don’t prevent illness, schools don’t prevent ignorance”. “Don’t confuse success in adapting to confinement with wisdom”.

Regardless of the end result, this is a very nice initiative that, come to think of it, couldn’t have been better, simply because even if proverbs are born as “the wit of one”, their edges are roughed out and their references are consolidated only by the “wisdom of many”. I didn’t do a better job myself. In the “Proverbs by you” blank pages at the end of the of book, I wrote three proverbs: “Conflict requires immediate attention, but only time can bring true resolution”. “To know oneself is also to make oneself”. “The antidote to negativity is not positivity, but warmth” (I stole this one from Facebook). Not quite masterful, eh? I like them because they speak to me, and they took shape as I battled writing the thesis and seeing a shrink (for the first time in my life). But they could have been better, too.

In the preface, Day-Woods admits that some of the proverbs in the collection “might already exist, are derivative […], won’t pass the test of time or are idiosyncratic[…]”. He goes further: “some will be misunderstood, some will be challenged or be scoffed at for various weaknesses”. I have done all of these things in this review, I guess. I do think some of them could be cut out (the number of proverbs was based “on the number of intersections of the Go board” – that might explain why some feel like filler), and a lot could be improved. But this was never up to Day-Woods, was it?

Just today I was reading a book of texts published in the early 20th-century Brazilian anarchist press by Isabel Cerrutti (1886-1970). She mentions going to a lecture and hearing Maria Lacerda de Moura repeat something that goes (translated) a little like this: “Peace among us, war against those who exploit men!”. Funny – I recognise that from protest chants, but it’s a little different; “Peace among us, war against the lords”. So the version that reached my generation is a little simpler, and thus a little more elegant. And it’s probable that de Moura didn’t create it in the first place either (edit: yep – apparently she did not).

It was never up to Day-Woods because it’s not really an individual process. It’s a collective, never-ending attempt to condense radical sensibilities into practical truth. With this book, I think Day-Woods and Herdman have contributed a lot to this beautiful endeavour.